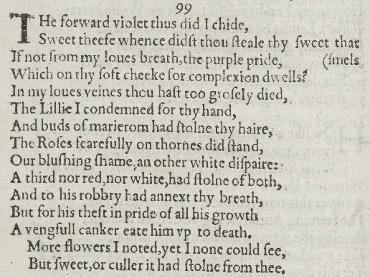

Sonnet 99 by William Shakespeare relates to the year 1599 as it is the only Shakespearean sonnet with fifteen lines, “a summer’s story” in fact encompassing a group of three sonnets 97, 98 & 99, which allude to a period when the young princes Robert Devereux (Essex) & Henry VVriothesley (Southampton):

“Hath put a spirit of youth in everything”.

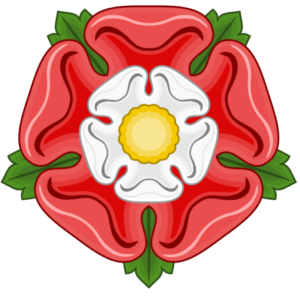

Lines 6 & 8 show the words “Lillie & Roses” capitalized – alluding to the Tudor Dynasty, while more disconcertingly in the last line we find the word “culler”.

In trying to understand our great author’s meaning – we must always look at the ‘quarto’ original (above) which helps us understand why these works relate to Essex & Southampton who are of course ‘Tudor Princes’, which we may determine because the words “Lillies” & “Rose” (S.98) and “Lillie” & “Roses” (S.99) are four words all capitalised in the quarto originals – the natural colours of Tudor England, which in this instance allude to Tudor princes. While in examining line ten of (S.99) we find an individual who is not of the House of Tudor – being neither “red nor white”, this is our mischievous author having a bit of a dig at the aristocratic pretensions of William Cecil (Lord Burghley) who became increasingly ill in the final period of his life and quite possibly died of cancer in the year 1598 – making perfect sense of the following line written by one of his principal adversaries:

“A vengeful canker ate him up to death”.

While what initially was “stolne” (line ten) from these two princes was in fact nothing tangible but something far more valuable indeed – reputation.

Let me quote Shakespeare from Othello:

Iago: “Who steels my purse steals trash ‘Tis mine, tis his, and has been slave to thousands, but he that filches from me my good name robs me of that which not enriches him and makes me poor indeed.”

“Heavy Saturn” line four (S.98) naturally is a further allusion to Cecil, let me quote ‘Katherine Duncan-Jones’:

“The planetary deity Saturn is associated with old age coldness and disaster, here he is seen as heavy in the sense of ‘grave’, ‘ponderous’ or ‘slow, sluggish’.

Queen Elizabeth I – along with Edward de Vere are known to have used the word “Pondus” a marsupial of the word ‘ponderous’ to describe Cecil – who finally reached his leaden tether on the 4th August ‘1598’.

During the period of this “summer’s story” the English had been trying unsuccessfully to gain the upper hand in Ireland, ‘Essex’ (Earl-Marshal) blamed the ‘Cecil-succession’ as he felt his troops insufficiently supported by the mother country. They were short of all essentials, food, clothing and armaments and he railed against the authorities explaining that they simply did not understand the conditions they were having to endure and fight under across the Irish-Sea.

If we take a brief look at “The Phoenix and the Turtle” which I have made a study of in my work “With the Breath thou Giv’st and Tak’st” it will help explain how we may recognise in these sonnets the young princes the 2nd Earl of Essex – Robert Devereux & the 3rd Earl of Southampton – Henry VVriothesley.

Observing the ‘quarto’ edition – in the first five stanzas (the injunction) of the poem – we find a parliament of birds represented in the following order: ‘The Phoenix, the Owl, the Eagle, the Swan and the Crow’, momentarily though we are only interested in the ‘eagle’ and the ‘swan’ for they are allusions to our proud young princes, meanwhile the poem cunningly creates the impression that what is presented to us is a requiem for “The Phoenix and the Turtle” but this is not strictly so, because the “session interdict” that is mentioned actually relates to an illegal memorial ‘service’ that shortly followed the Essex execution.

A Poetic Palette. (Its principal colours red, white & purple)

There are only two words found within the ‘injunction’ of ‘The Phoenix and the Turtle’ both capitalised & italicised, they are the words “Arabian” (in the first stanza) the elaborate ‘A’ deputising for the initial of the God ‘Apollo’ while in the (fourth stanza) the elaborate ‘R’ of “Requiem” deputises for the first-initial of ‘Robert Devereux’, because in death Essex (a poet) becomes a Swan (one of Apollo’s birds). While interestingly, we can individually identify our two princes in ‘proper’ Tudor colours and by looking more broadly at the Shake-speare cannon – also identify our author in the colour green. While I fully appreciate – ‘The Tudor-Rose’ was originally designed to commemorate the marriage of Henry VII & Elizabeth – merging together the houses of Lancaster and York ‘red & white’, while in the third verse of “The Phoenix and the Turtle” we find ‘Henry VVriothesley’ represented by the ‘Eagle’ (his nickname to his closest friends) attracted because of his flamboyant dress sense and penchant for wearing tall feathers in his hats, while in Titus Andronicus we find this king of birds the Eagle “suffers little birds to sing”.

His colour is red.

This is the 11th line of the poem (The Phoenix & Turtle-dove) and the original spelling:

“Save the eagle, feath’red king”. (Quarto)

John Donne alludes to this very fact in his poem “The Canonization”.

“And we in us find the ‘Eagle and the Dove;

The Phoenix riddle hath more wit

By us, we two being one, are it.”

The Hebrew word for God is ‘One‘.

Found in Zechariah Chapter 14 Verse ‘IX’. And the Lord shall be King over all the Earth: In that day there shall be one Lord, and his name is One.

In a pattern of his love ‘Donne’ alludes to ‘The Tudor Trinity’ who are ‘VVriothesley (One) Elizabeth (The Phoenix) and Oxford (The Dove) While in the fourth verse of (P & T) ‘Robert Devereux’ is represented by the ‘Swan’ because in death like Orpheus he became sweet creation – Apollo’s bird.

His colour is white.

This is the thirteenth line of the poem:

“Let the priest in surplice white”.

This allusion is confirmed in line twelve of (S.97.)

“And thou away, the very birds are mute”.

Yes; the principal colours of the Tudor Rose are ‘red & white’ but the third colour is green – which is where our author comes in, he is Henry VVriothesley’s father and Queen Elizabeth his mother, and by reading the finale of his poem “Venus & Adonis” we understand it an allegory of VVriothesley’s miraculous birth, in that sense this same subterfuge is repeated in “Loves Martyr” where the birth of rare ‘VVriothesley’ again takes place without any rumpy-pumpy having taken place, because the ‘Phoenix and the Turtle’ reproduce by immolation (throwing themselves upon a funeral pyre).

The purpose of these tales is to save the virgin Queen’s blushes, because what would make a sexual relationship between “The Phoenix and the Turtle” illicit – is these birds allegorise English princes (members of the same family) by representing Queen Elizabeth I (the Phoenix) and Edward de Vere the 17th Earl of Oxford (the Turtle).

The 17th Earl of Oxford Edward de Vere and Queen Elizabeth are found quite easily in his ‘avian’ poem because he cleverly subjected himself to certain mathematical criteria when writing it, some of which I will now reveal to you, most simply; at the time of publishing (the summer of 1601) we find Elizabeth was 67 years old, which is precisely why the poem is composed of sixty-seven lines, while Interestingly we also find the penultimate verse (the 17th verse) constructed of precisely 17 words, although more conclusively and more interestingly we discover exactly who the turtle is when counting the amount of ‘T’s in the 5th Stanza – beginning in the 17th line!

(17) And thou treble dated Crow,

(18) That thy sable gender mak’st,

(19) With the breath thou giv’st and tak’st,

(20) Mongst our mourners shalt thou go.(Stanza 5 P&T)

That’s 17 ‘T’s.

While it might be worth noting that the aggregate number of ‘T’s in the remaining 17 stanzas is 9.

Unfortunately, what is more shocking – is the meaning of line ‘XIX’.

“With the breath thou giv’st and tak’st”.

Here our great author rather spills the beans – because the following is its meaning:

When Robert Devereux 2nd Earl of Essex became the illegitimate issue of the Virgin Queen ‘she gave him breath’ and when she signed his execution warrant and he was executed ‘she took his breath away’.

If you think that bad? Then unfortunately I have even worse news; regarding incest.

If Rumours spread in Elizabethan times about envious ‘Essex’ and ‘Elizabeth’ being lovers were true, then that obviously represents incest. To my mind though; there is much more certainty about the incestuous relationship that existed between Elizabeth and Edward de Vere, though before explaining this, I should credit those proponents Paul Streitz and Charles Beauclerk who in their respective books elaborated on the earlier ideas of J.Thomas Looney & Percy Allen in promoted ‘The Prince Tudor Theory’.

My belief, is also – that Elizabeth gave birth to “The first” of her sons (Edward de Vere) shortly before her 15th birthday on July ’14’ 1548. Shakespeare’s sonnet ’14’ confirms this fact – as it begins with an astrological allusion:

Not from the stars do I my judgement pluck, And yet me thinks I have Astronomy. (S.14)

In ‘Love’s Martyr’ the host work for “The Phoenix and the Turtle” there is a poem by our great author explaining this very fact – a poem pertinently entitled “The first”, which appears on the page immediately preceding his avian masterpiece.

Having read the fore mentioned books; I was left intrigued but open-minded, it was only on completion of my study of ‘Loves Martyr’ that I became convinced of this reality, that ‘Oxford’ was Elizabeth’s son.

Edward de Vere wrote using hundreds of different pseudonyms, one of which was the witty ‘Robert Chester’ which in signing the dedication to Sir John Salisbury in “Love’s Martyr” he more realistically reduced to “Ro.Chester”, thereby alluding to the city in Kent we know today as “Rochester“. This is the place where on the 21st May 1573 his very favourite (true) story unfolded – when his men robbed the Lord Chancellor William Cecil’s men at Gads Hill on the road between Gravesend and Canterbury just outside Rochester! He later bought the date of this robbery forward a day – so it celebrated the most important day of his life on every occasion, he spoke, or wrote of it. Sonnet 20 confirms exactly what I am saying – as it is a portrait of his son the androgynous prince Henry VVriothesley referred to (dead-centre) in the quarto of (S.20) as “Hews” which is a marsupial of his name ‘Henry VVriothesley’ and the only word in the sonnet both capitalised and italicised!

Evidence is found in “Love’s Martyr” that Robert Devereux (Essex), Edward de Vere & Henry VVriothesley who are referred to in the dedication to “Love’s Martyr” as “Envie, Every One” were not the only three illegitimate Elizabethan princes, as there is further evidence identifying ‘five princes’, names revealed in my article “With the Breath thou Giv’st and Tak’st”.

Also explained therein, are the spellings of the words feathered & chequered, in “The Phoenix and the Turtle” we find “feath’red”, and in “Venus & Adonis” we find “chequ’red” in both cases these words are paired with the word ‘white’ because they are Tudor colours, and our proud author is keen to bring our attention to this fact. While his highly successful poem “Venus and Adonis” from 1593 was the first work published using the brand ‘William Shakespeare’.

“Thence comes it that my name receives a brand”.(S.111).

‘Adonis’ is of course an allegory of our author Edward de Vere, ‘Venus’ an allegory of Queen Elizabeth, while we see at the conclusion of the poem ‘Adonis’ slain by the wild-boar, who quite incredibly gets more than just the one mention – in fact the blue boar which the ‘de Vere’s’ wore on their helmets in battles through times immemorial gets mentioned exactly ‘17 times’. While at the poem’s denouement Adonis is slain when the boar’s tusk penetrates his crown jewels, while ‘Venus’ is so distraught she closes her eyes in disbelief – before fearfully reopening them:

|

1051 |

And, being opened, threw unwilling light |

|

1111 |

“Tis true, tis true!” Thus was Adonis slain: |

When ‘Adonis’ is fatally wounded the blood he bleeds is purple – the reason being our author was royal, while towards the conclusion of this allegory we receive further proof of this – as the poem’s palette is awash with red & white colours symbolising the Royal Tudor dynasty.

|

1165 |

By this, the boy that by her side lay killed |

|

1171 |

She bows her head, the new-sprung flower to smell |

Having personally cropped the stalk of a ‘Fritillary’ I can confirm that in its breach green sap appears – although rather pale, while it is certainly a purple flower chequ’red with white – which most obviously represents our proud prince, Henry VVriothesley.

From the front-piece of John Gerard’s ‘Herbal’ first published in 1597 – showing ‘Adonis’ (with curly hair) wearing a wreath of bays while holding a ‘Fritillary-Flower’ aloft, an allusion to his royal son.

What I wonder is if “green dropping sap” is a clue to our author’s paternity of VVriothesley – because by looking once again at “Love’s Martyr” we may deduce that his livery was ‘Vert’ (green) because during the “Invocation” to “Diverse Poetical Essays” that accompanies “The Phoenix and the Turtle” we find Elizabeth “In the height of Grace” invites:

The ever-youthful Bromius to delights,

Sprinkling his suit of Vert with Pearle.

Now, it is possible to interpret these two lines as being rather ‘seedy’ something I can confirm with a collaborative quotation from “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” which in this instance appears a wet one.

Tomorrow night, when Phoebe doth behold

Her silver visage in the wat’ry glass,

Decking with liquid pearl the bladed grass

(A time that lovers’ flights doth still conceal).

Act 1 Scene 1 – 209

These Lovers are of course ‘two’ and the same = Venus & Adonis, The Phoenix and the Turtle, Queen Elizabeth I of England and the 17th Earl of Oxford Edward de Vere.

Colour-wise (in a somewhat playful sense) our Virgin Queen can be found dead centre of the ‘Tudor Rose’ as her hair is mirrored by the Marigold flower – ‘John Lily’ Edward de Vere’s personal secretary said this:

“She useth the Marigold for her flower,

which at the rising of the sunne openeth

his leaves, and at the setting shutteth them”.

The Cecil’s as ‘Cullers’ of Princes.

A principle & prevailing thought of mine is that when our great author like his esteemed friend Dr John Dee put pen to paper, they didn’t make mistakes (though admittedly compositors did). So, where in the last line – we find the word “culler” I am resolute, what our author meant was precisely that. While to my knowledge; this is the only instance of Shakespeare using this particular conjugation of the verb.

Therefor in explanation let me quote lines 5 to 8 of (S.98).

(5) Yet nor the laies of birds nor the sweet smell

(6) Of different flowers in odor and in hew

(7) Could make me any summer’s story tell,

(8) Or from their proud lap pluck them where they grew.

The word he uses at the end of line six is “hew” not ‘hue’ while the only thing that surprises me about this is that the word “hew” is not capitalised, as obviously it is an allusion to ‘Henry Wriothesley’. While our author speaks of “different” flowers (line 6 S.98) some ‘odoriferous’ and some princely flowers ‘roses’, therefore we can divide them into two groups.

1. Vengeful & odoriferous flowers (nor red nor white) or:

2. Sweet ‘red & white’ Tudor flowers (princes).

This first group saw it their duty to pluck or cull the second group where they grew – they were therefore ‘cullers of colour’ because by reducing the population of princes by selective slaughter the person or persons responsible for this action could be termed ‘culler’ the very reason our author uses this word in the final line of (Sonnet 99).

In our author’s eyes ‘Essex’ was culled – although in all probability he was not the only Tudor prince culled, for it is a little-known fact that he had a brother called ‘Arthur Dudley’ also conceived by ‘Elizabeth’ and her favourite ‘Leicester’.

In the year 1587 at the age of 26 or so, this particular prince found himself presented to the court of ‘Philip II’ following his capture from a shipwreck off the coast of Spain. The Spanish court were so taken by his story they granted him a pension, while understandably the court in London saw this behaviour as treacherous. Following this episode – his persistent bragging in the Iberian Peninsula (regarding his royal heritage) soon saw English agents sent to work – while sometime afterwards he found himself wiped off the face of the earth – terminated – vaporised – culled!

Sonnet 99 also identifies these Royal Princes because our author wears spectacles tinted with purple-hues (spelled ‘Hews’ in S.20) a marsupial of the name Henry Wriothesley, but not only is our author’s sight corrupted by love – but also his sense of smell.

(1) The forward violet thus did I chide:

(2) Sweet thief, whence didst thou steal thy sweet that smells,

(3) If not from my loves breath, the purple pride

(4) Which on thy soft cheek for complexion dwells?

(5) In my loves veins thou has to grossly dyed.

There exists here, something that could be termed ‘floral-impudence’ because in the beginning we note the violet is forward – its perfume stolen from the fair-youth’s breath (VVriothesley’s breath.) Of course the predominant point our author seeks to convey to his audience is not that of his own royalty but VVriothesley’s. This ‘purpleness’ found in the violet is infused in VVriothesley’s veins – expressed by our author as “purple-pride” which is the royal-blood running through his veins. This ‘floral-impudence’ continues because the whiteness of the lily is a poor representation of the royal hand, while we find amongst this floral cabal – buds of Marjoram (which can be purple) have stolen our princes hair!

In line (6) we find the suggestive words “condemned hand”, alliteration for ‘condemned man’ (Essex) small wonder then in line (11) that we find VVriothesley’s breath “annexed”.

The Earl of Essex – his caparisoned white horse adorned with white plumes. His hair tightly curled like buds of marjoram (which can be purple). While worth noting – is the black & white (chevron) livery of his groom (black & white being the Queen’s colours).

(6) The lily I condemned for thy hand,

(7) And buds of marjoram had stol’n thy hair;

(8) The roses fearfully on thorns did stand,

(9) One blushing shame, another white despair.

‘Our princely roses’ (divinely ordained in Heaven) cleverly appear in line (9) or ‘IX’ the number most associated with Christ. Though they had run into a bit of trouble with the woman who “wrought” them into this world (S.20 L.10). Essex against Elizabeth’s command had made VVriothesley his ‘master of the horse’, she had also expressly ordered him not to leave Ireland without her permission, but in late September 1599 with a small posse of men to protect him – that is exactly what he did.

Essex was going to have it out with the Queen (not for the first time) he was going to give her a piece of his mind, consequently on the morning of – September 28th 1599 he famously broke into her bedchamber (muddy boots ‘n’ all) when she was only half attired – even before dressed with her wig – actions from which he soon found himself under house-arrest with many serious charges levelled against his person.

His predicament with its potential for further censure and demise by execution sent him into a steep psychological and physical decline, therefor with this new calamity:

The roses fearfully on thorns did stand,

One blushing shame, another white despair.

These two lines are most obviously allegorical. In fact, I would say without the allegory – they don’t make proper sense, because how can roses be fearful? Having said that, if of course the word ‘roses’ is a substitute for the word ‘princes’ then these two lines make perfect sense, as we find our fearful ‘red & white’ princes – in a state of ‘nervous anticipation’ which is one way of explaining “on thorns did stand” or another way is by quoting ‘Jonathan Bate’ “in a state of high anxiety”.

Robert Devereux’s ‘Impressa’

Robert Devereux’s ‘Impressa’

Here we find “Essex” wearing the Black and white colours associated with his mother (Queen Elizabeth I). His doublet with a black and white scheme has a chevron pattern not unlike the livery of his groom. While the shape of his cloak may allude to his ‘personal-Device’ which is a sable-shield emblazoned with the words:

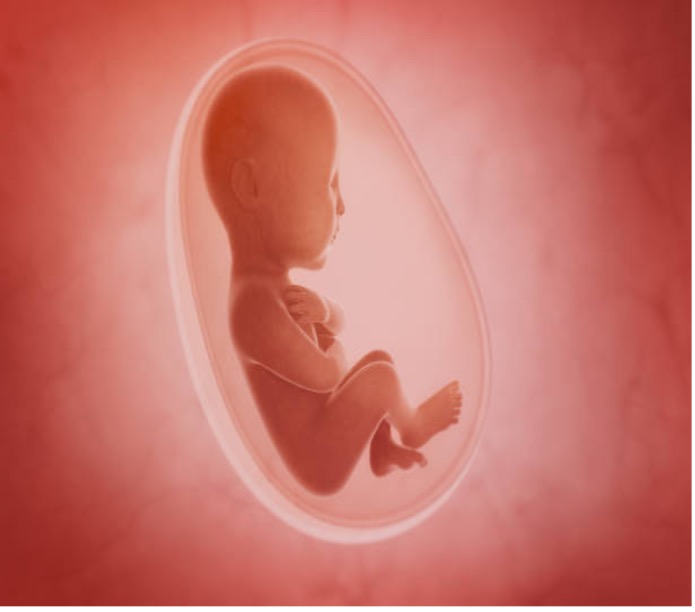

“Par-Nulla-Figura-Dolori”

Which has the Ironic meaning: ‘Nothing can represent sorrow’. As we see his hand held upon his Heart – half secluded by his cape, perhaps suggesting a forbidden love. This ‘Impressa’ represents Robert Devereux’s life – it is a biographical snapshot of his transition (body & soul) into this mortal world, while in interpreting its unusual oval-form we find a message both pre-natal & postnatal. The ‘motto’ of an ‘impressa’ should be in a foreign language (in this case Latin) and should according to ‘William Camden’ ‘be wittie, short and neither too obscure nor too plaine, and should notify some conceit regarding its donor’.

The motto adorning Robert Devereux’s ‘impressa’ is: “Dat poenas laudat fides” which may translate to “My praised faith procures my pain”.

As we have already seen William Shakespeare’s ‘Venus & Adonis’ is simply awash with ‘red & white’ symbolism, an Elizabethan allegory concluding with the birth of Henry VVriothesley:

“A purple flower sprung up chequ’red with white”.

In fact, in later life these popular young princes (hardly offended by their Royal DNA) found themselves royal privilege by wearing silk-white. Though ultimately when they were convicted of crimes against the state and incarcerated in the tower, they had no immediate use for them. Therefore, in Stanza four of “The Phoenix and the Turtle” where we find the words “Surplice-white” used, we also find a great witticism.

Henry VVriothesley the ‘Eagle’ wearing royal silk-whites.

Though Henry VVriothesley may be associated more closely with ‘red & white’ symbolism, we see from the ‘impressa’ of Essex his colours are ‘black & white’, colours undeniably associated with constancy and purity – mythical virtues relating to his mother the virgin Queen.

In the subsequent stanza of “The Phoenix and the Turtle” (the fifth) we find Elizabeth approaching death – racked with remorse in respect of her own son’s execution, and because of the dreadful guilt she felt, in decline a duel with both insanity and despair began, in which at “fevers end” death became the ultimate victor. Once in her prime she was a beautiful Phoenix with purple, red & golden plumage, while in line (17) of the poem – in old age (treble-dated) she bore a deathlier look.

Elizabeth as: “The Treble Dated Crow”

Elizabeth as: “The Treble Dated Crow”

In Shake-speare’s mythology ‘Venus and Adonis’ reproduce miraculously as do ‘The Phoenix and the Turtle’ – which is why the ‘crow’ fits seamlessly into our author’s world, for it too was believed to have reproduced ‘chastely’ through a touching of beaks & exchange of breath.

(17) And thou treble-dated crow,

(18) That thy sable gender mak’st.

“Sable gender” is precisely what the virgin Queen produced (surreptitiously) in giving Robert Devereux breath, for his ‘device’ was ‘sable’ (the heraldic term for black) something we see reflected in his ‘impressa’ in the shield-shaped cloak draped over his shoulder. Meanwhile, our all-knowing great poet needed a sharp intake of breath – before musing upon the demise of his own half-brother in line (19) an allusion to ‘Jesus Christ’, words creating pathos that when fully understood – that will surely shake the cobwebs of old Tudor England.

For those of you who have studied Envious Essex; I would like to make a concise and overriding observation about his errant behaviour – explaining his eccentric ways. To my mind, he displayed absolutely the disenfranchised psyche of an illegitimate prince, for all he ever really wanted – was his mother to identify him as legitimate, because all illegitimate princes found themselves deeply disturbed by the reality that although they were royal – they were also royal bastards. In literature there is possibly no greater expression of this than found in the dialogue of Shakespeare’s play ‘King Lear’ a title interestingly rhyming with ‘Vere’, of which ‘Sigmund Freud’ said in a letter posted from Vienna to Percy Allen on the 7th November 1935:

“It only made sense psychologically on the assumption that it was written by the 17th Earl of Oxford Edward de Vere”.

Before going on to say:

“I believed he was responsible for all the other genuine Shakespeare plays”.

While we find Oxford (arguably the greatest Englishman that ever lived) for all his genius, education and intellect, was himself born out of wedlock and like Essex in all probability seduced into incest by his very own mother.

Incest wasn’t something Elizabeth had only a mild flirtation with, for at the age of eleven (when literally still a virgin) she found herself seduced by some colourful literature coming to her courtesy of Marguerite Angouleme (sister of the king of France) bought to England by her mother Anne Boleyn. Then following a study and translation of this work “The Mirror of the Sinful Soul” she ultimately discovered through incest she could increase her own power and domination over men – making the chosen few literally enthral to her.

In terms of the possibilities of womanhood ‘Elizabeth’ was ‘everything’ to ‘Oxford’, the reason he described himself “Pent” within her (S.133 L 13) – meaning there was no possibility of him escaping the way she began his life & continued to dominated it. He was delivered to her “The first” prince, and in the guise of “fortune” she organised for him one of the greatest educations anyone ever received, while later protecting him (denying his wishes) to go to to war (S.25 L 3 & 4). She was the Queen who made him court-poet, she was his employer, his paymaster, his lover, while he in turn danced with her through the night, wrote sonnets for her, and composed music she played on the lute – but more frequently on the virginals:

How oft, when thou, my music play’st

Upon that blessed wood whose motion sounds

With thy sweet fingers, when thou gently sway’st

The wiry concord that mine ear confounds,

Do I envy those jacks that nimble leap

To kiss the tender inward of thy hand,

Whilst my poor lips, which should that harvest reap,

At the woods boldness by thee blushing stand,

To be so tickled, they would change their state

And situation with those dancing chips

O’er whom thine fingers walk with gentle gate,

Making dead wood more blessed than living lips,

Since saucy jacks so happy are in this,

Give them thy fingers, me thy lips to kiss.(S.128).

Elizabeth’s “store” of ‘spare’ princes all felt this same subjugation, and because she remained to her subjects a virgin till her dying day our author felt at liberty to describe in (S.97) this “abundant issue” of princes as “orphans” also terming them “unfathered fruit”, simply because if your mother was a virgin-queen – it was consequently impossible for you to have a father.

In my previously mentioned work “With the Breath thou Giv’st and Tak’st” I explain how ‘Oxford’s’ friend John Dee – before ‘Spring 1601’ had prophesied the dates of the following:

(1) Queen Elizabeth’s death (1603)

(2) Edward de Vere’s death (1604)

(3) The date the Globe-Theatre burned to the ground (1613).

Three prophesies that may be an expression of ‘Sacred 3‘.

Consequentially, our great author saw the opportunity of being able to spill the beans in respect of his Royal DNA, as Dee’s prophesy correctly predicted that Elizabeth would die fifteen months before he did.

As I have said; the meaning of Oxford’s poem “The first” which is embellished with his ‘triangulated anagrammatic signature’ is that he was Elizabeth’s first-born son.

In black & white, Essex similarly spills the princely beans by producing his miniature ‘impressa’, it being composed in an unusual mannerist-oval format, drawing our attention to what once was an immaculate Royal womb – before the ambitious, lusty (and fertile) Lord admiral ‘Thomas Seymour’ went to live in the same ‘Chelsea Manor House’ that princess Elizabeth shared with the Dowager Queen Katherine Parr. Elizabeth like ‘Juliette’ was 13 years old when first seriously wooed by Thomas – he wasn’t! Though interestingly, in a reverse marsupial of sequential letters found within his name she had also found her ‘Romeo’ (THOMAS SEYMOUR).

Elizabeth’s heart beat faster and she was said to blush any time his name was mentioned and both she and her staff were subsequently called by the Lord protector (Thomas Seymour’s brother Edward) to account for the persistent rumours that said; he had fathered an infant with her (Kat Ashley & Elizabeth’s cofferer ‘Thomas Parry’ both being held in the tower during their depositions). The possible truth then, is that at approximately the same time Thomas Seymour impregnated his wife, he also impregnated Elizabeth, which is why when Kathrine Parr left London with her entourage travelling to Sudeley Castle in Gloucestershire for her lying in – Elisabeth mysteriously went in an opposite direction – to Cheshunt in Hertfordshire, where she stayed in seclusion for more than four months. One does wonder why she was parted from the woman she liked to call ‘mother’ at a time we imagine Katherine would have found her company comforting. While the real reason for this parting of the ways is a documented fact, Katherine had caught the Admiral & Elizabeth in a ‘close embrace’ – following which the Queen: “Fell out, bothe with the Lord Admiral and with her grace also”.

Romeo & Juliet meet on Edward de Vere’s TRUE Birthday.

As stated previously ‘Oxford’ wrote using many, many different pen-names, one of which was ‘Ignoto’ (the unknown) in Latin.

In his book “The Poems of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford” by ‘J. Thomas Looney’ he includes eleven of these poems; signed ‘Ignoto’ so, it is difficult to argue against this fact.

In the quarto of ‘Loves Martyr’ preceding his untitled poem “The Phoenix and the Turtle” which deliberately appears on page “170” we find two further renditions sharing the honours on the page prior (quarto Pg. 169). The second of these “The burning” is signed ‘Ignoto’ a beautiful mythological eight-liner championing the death of the ‘Phoenix’ (Elizabeth) by immolation and rebirth as a ‘rare’ new ‘Phoenix’ (VVriothesley) a poem that does of course represent the dreams of our great author. ‘Sacred 3’ raises its head in the final rhyming couplet, with the word “rare” occurring twice and the word “One” occurring once. “One” being the Hebrew word for ‘God’.

Her rare-dead ashes, fill a rare-live urne:

‘One’ Phoenix born, another Phoenix burne. (Ignoto).

The first” of these two poems is anagrammatically signed “E de Vere”.

Let me therefore summarise these amazing & important revelations: On the page that precedes William Shakespeare’s famous metaphysical masterpiece “The Phoenix and the Turtle” we have two poems the title of “The first” informing humanity that the person known as “E de Vere” was the “The first” born son of Queen Elizabeth I – who ‘wrought’ him into this world shortly before her fifteenth birthday – when still a ’14’ year old princess.

The second poem begins with the word “Svppose” starting with a capital “S” for ‘Southampton’ followed by a capital ‘V’ for Vere, it is a poem in our author’s own words:

“Sweet’ning the inward roome of man’s De-sires”

Notice how the ‘D’ of Desires is capitalised – most obviously representing the ‘De’ in ‘De Vere’.

Returning to Romeo & Juliette, I believe it possible to determine Edward de Vere’s TRUE date-of-creation from some of the dialogue in the play – as I can fathom no other reason for some of the conversation between Lady Capulet and Juliette’s nurse when discussing Juliette’s age, the nurse stating that Juliette was not fourteen yet, verified by the following words:

“How long is now till Lamas tide?”

To which Lady Capulet replies:

“A fortnight and odd days”.

To my mind a fortnight and odd days – surely translates to 17 days, because odd days, most likely, must be three, three and fourteen make 17. So, I deduce from this figure that the author is alluding to himself, while we should bear in mind that Lammas-day is the 1st August, while the nurse continues:

“Even or odd, of all days of the year, come Lammas Eve at night shall she be fourteen.”

Therefore, Juliette’s birthday is the 31st July.

But the day of this conversation (the day of the Capulet ‘Mask’) where Romeo & Juliette famously meet is 17 days previous to Lammas Eve – the 31st July. Therefore Romeo & Juliette meet and fall in love on the 14th day of July.

So, excuse my romantic heart, but could this be the way Edward de Vere chose in literature to celebrate his TRUE date-of-creation 14th July 1548.

A fact is of course confirmed by the astrological allusion with which sonnet ‘14‘ begins:

Not from the stars do I my judgement pluck, And yet me-thinks I have astronomy.

This would mean Princess Elizabeth born (7-09-33) gave birth eight-weeks prior to her fifteenth-birthday, while the poetic rendition that immediately follows “The Phoenix and the Turtle” (Pg. 173) of ‘Loves Martyr’ known as “A Narration” informs us that she was responsible in total for the issue of five illegitimate princes (all male). So, an amazing statistic deducible from this likelihood is that the woman known to us today as the Virgin-Queen could have spent a maximum of One thousand four hundred days of her life being pregnant! Hardly surprising then, that women at court constantly being prevailed upon by virile sonneteers – chose to wear clothes designed to conceal away any such embarrassments of ‘nature’.

Conversely, women proud to be pregnant – sometimes commissioned pregnancy portraits, the accompanying painting (which is draped in symbolism) is one such work, a practice adopted in Elizabethan times because of the extremely high levels of both mother & child mortality during and after child birth. The upside of this practice being that in the event of death such a portrait could become a remembrance of maternity and happier times. Also, with good reason – it has been suggested this ‘pregnancy portrait’ depicts Elizabeth carrying ‘Francis Bacon’ a further suggestion being that ‘Francis Walsingham’ was the father of the child, while it is interesting to know, that Francis Bacon referring to himself and his princely brothers used the expression enfans perdu “The lost Children”. This picture painted by Marcus Gheeraerts held in the Royal collection, when seen in 2006 at Hampton Court by Charles Beauclerk was described as “Shakespeare’s Dark Lady”. It is also worth remembering that all these Tudor Princes had not only official and unofficial birthdays but also official and unofficial names, consequently our great author’s official name was Edward de Vere while his real-name was ‘Edward Tudor’, while Francis Bacon’s real name was ‘Francis Tudor’. Henry Wriothesley was named after his grandfather ‘Henry VIII’ and if he had acceded to the throne of England he would have become ‘Henry IX’, a number intrinsically related to ‘Jesus Christ’ and no doubt part of the reason this dream (of Kingship) was kept alive in the mind of his mortal father.

Conversely, women proud to be pregnant – sometimes commissioned pregnancy portraits, the accompanying painting (which is draped in symbolism) is one such work, a practice adopted in Elizabethan times because of the extremely high levels of both mother & child mortality during and after child birth. The upside of this practice being that in the event of death such a portrait could become a remembrance of maternity and happier times. Also, with good reason – it has been suggested this ‘pregnancy portrait’ depicts Elizabeth carrying ‘Francis Bacon’ a further suggestion being that ‘Francis Walsingham’ was the father of the child, while it is interesting to know, that Francis Bacon referring to himself and his princely brothers used the expression enfans perdu “The lost Children”. This picture painted by Marcus Gheeraerts held in the Royal collection, when seen in 2006 at Hampton Court by Charles Beauclerk was described as “Shakespeare’s Dark Lady”. It is also worth remembering that all these Tudor Princes had not only official and unofficial birthdays but also official and unofficial names, consequently our great author’s official name was Edward de Vere while his real-name was ‘Edward Tudor’, while Francis Bacon’s real name was ‘Francis Tudor’. Henry Wriothesley was named after his grandfather ‘Henry VIII’ and if he had acceded to the throne of England he would have become ‘Henry IX’, a number intrinsically related to ‘Jesus Christ’ and no doubt part of the reason this dream (of Kingship) was kept alive in the mind of his mortal father.

In the bottom right-hand corner of the above portrait, we have a cartouche within which there is a sonnet written in the Shakespearean format (three stanzas plus a rhyming couplet) which should be entitled: “My Weepinge Stagg I Crowne”. This is the first stanza:

(1) The restles swallow fits my restles minde (35 letters)

(2) In still revivinge still renewinge wronges; (37 letters)

(3) Her just complaintes of cruelty vnkinde (34 letters)

(4) Are all the musique that my life prolonges. (35 letters)

Total = 141 letters.

In conjunction with either the classical-Latin or Elizabethan alphabets (they are the same until the 20th letter) by using simple Hebrew gematria, 141 letters translate into the name:

‘Francis Tudor‘.

67 is arrived at because: F = 6. R = 17. A = 1. N = 13. C = 3. I = 9. S = 18.

74 is arrived at because: T = 19. U = 20. D = 4. O = 14. R = 17.

We must therefore realise that when it came to the virgin-queen’s love-life it wasn’t so much ‘chilly and quaint’ but more ‘chili-quaint’, a promiscuity to which she almost admits in a book of personal prayers published in Latin when she was 30 years old, at a point in her life to which those that – knew her – would have described her as being in her prime.

It would then, be appropriate to remind you of just one of these prayers:

From my secret sins cleanse me;

From the sins of others spare your handmaid.

Many sins have been forgiven her because

She has loved too much.

Here I would like to point out the blindingly obvious that ‘love is a virtue not a sin’. Then in returning to Nicholas Hilliard’s womb-like ‘impressa’ painted on vellum, we recall the predominant colours black & white symbolising both Elizabeth and her Envious son Essex, while the emotion perceived by the viewer is the “white despair” of a lovelorn prince – who both literally and metaphorically found himself constricted by Elizabeth’s thorny white Eglantine Rose pinning the youthful sonneteer to a more stout and steadfast-tree, as we remember Christ before death wore a crown of thorns.

Philip Cooper fecit: © 18th April 2021.