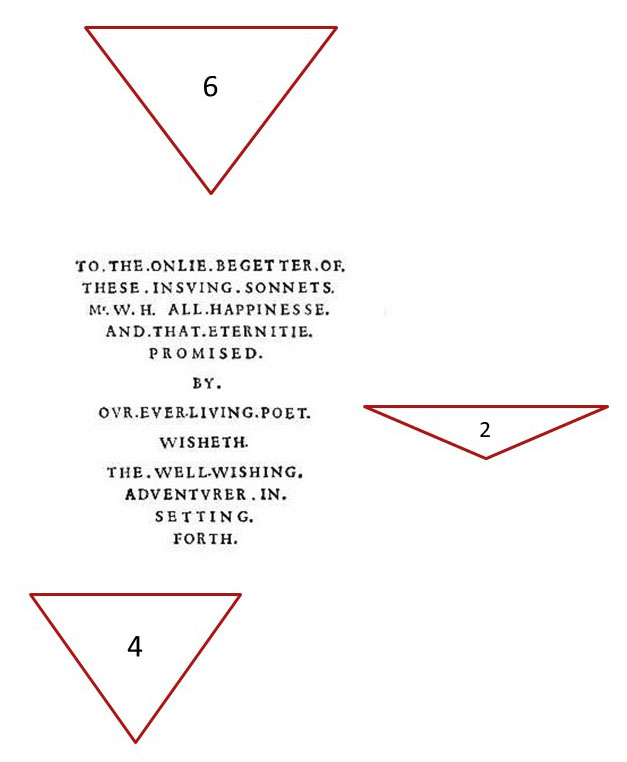

It can be seen in this late 15th century painting of ‘God the Father’ by Antoniazzo Romano that the conventional Christian halo has been replaced by a triangular one, representing the holy trinity – The Father the Son and the Holy Ghost. The Tudor-Trinity. Call-me-naïve, if it’s your will – but to my mind what is possibly a greater work of renaissance art, highly complex in construction and undeniably the work of a genius is William Shakespeare’s dedication to his sonnets, a work also based on the geometry of the triangle, although in its case the triangle represents ‘The Tudor-Trinity’ whose protagonists are the fair youth, the dark lady, and the author, a trinity described by Shake-speare in his invention (Sonnet 105) as ‘three themes in one.’ The sonnets are Shake-speare’s pre-eminent work – Opus No. 1, marked by tradition at their outset with the invocation of the nine muses (expressed in the following diagram by the vertices of three triangles.) Our star of poets ‘tongue-tied by authority’(S66) found through necessity, he needed to create what he called his ‘invention’ (S76) (his own idiosyncratic language) which he used as camouflage from behind which he expressed a true story, often termed the greatest love in literature, his love for the fair youth. The following diagram expresses how the author anticipated his readership visualizing his sonnet’s dedication. The numbers represent the sum of lines of text, numbers which also represent the author.

It can be seen in this late 15th century painting of ‘God the Father’ by Antoniazzo Romano that the conventional Christian halo has been replaced by a triangular one, representing the holy trinity – The Father the Son and the Holy Ghost. The Tudor-Trinity. Call-me-naïve, if it’s your will – but to my mind what is possibly a greater work of renaissance art, highly complex in construction and undeniably the work of a genius is William Shakespeare’s dedication to his sonnets, a work also based on the geometry of the triangle, although in its case the triangle represents ‘The Tudor-Trinity’ whose protagonists are the fair youth, the dark lady, and the author, a trinity described by Shake-speare in his invention (Sonnet 105) as ‘three themes in one.’ The sonnets are Shake-speare’s pre-eminent work – Opus No. 1, marked by tradition at their outset with the invocation of the nine muses (expressed in the following diagram by the vertices of three triangles.) Our star of poets ‘tongue-tied by authority’(S66) found through necessity, he needed to create what he called his ‘invention’ (S76) (his own idiosyncratic language) which he used as camouflage from behind which he expressed a true story, often termed the greatest love in literature, his love for the fair youth. The following diagram expresses how the author anticipated his readership visualizing his sonnet’s dedication. The numbers represent the sum of lines of text, numbers which also represent the author.  Although absolutely ingenious, the sonnet’s dedication could in some ways be considered subterfuge, because the most critical information the author is hoping to transmit to us, we only discover when we have untangled what has long been kept a secret – the fact that this dedication is encrypted. Immediately though the author shows us his great cunning in the biblical allusion which the first line represents. ‘To the only begetter,’ words originating as ‘One Lord Jesus Christ, the only begotten son of God.’ This allusion is particularly pertinent because not only does it attract us to the idea of ‘an only son’ but because our author also sees his son as having the celestial visage of a deity, believing he is divinely ordained (S154) ‘A little love God’ with golden hue, that illuminates all before him, who (S33) ‘flatters mountain tops with sovereign eye’, ‘kissing with golden face the meadows green’ while ‘gilding pale streams with heavenly alchemy.’

Although absolutely ingenious, the sonnet’s dedication could in some ways be considered subterfuge, because the most critical information the author is hoping to transmit to us, we only discover when we have untangled what has long been kept a secret – the fact that this dedication is encrypted. Immediately though the author shows us his great cunning in the biblical allusion which the first line represents. ‘To the only begetter,’ words originating as ‘One Lord Jesus Christ, the only begotten son of God.’ This allusion is particularly pertinent because not only does it attract us to the idea of ‘an only son’ but because our author also sees his son as having the celestial visage of a deity, believing he is divinely ordained (S154) ‘A little love God’ with golden hue, that illuminates all before him, who (S33) ‘flatters mountain tops with sovereign eye’, ‘kissing with golden face the meadows green’ while ‘gilding pale streams with heavenly alchemy.’

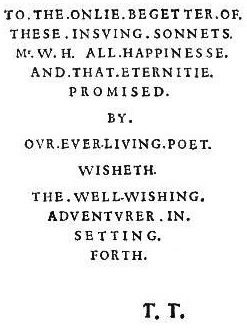

The Eccentric Facade of the Sonnet’s Dedication. Endorsed by the publisher Thomas Thorpe. – A true copy from the original –

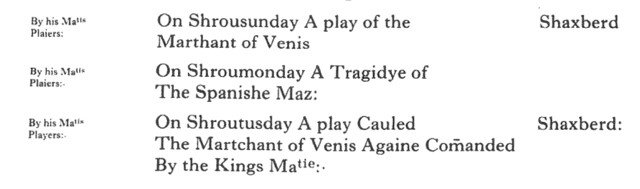

Having seen a good number of Elizabethan and Jacobean literary dedications I am obliged to say that there are no others quite like this – its format is unique. Which does prompt the question why? If we look a little closer, we see that every word is divided by a full-stop, the reason being that the author wishes us to count the words – which amount to thirty. The irregularities in spelling are another intriguing facet; these though are not eccentricities, but quite deliberate, for without these unorthodox spellings the cipher would not work. Though some would have us believe differently a polymath like Shake-speare didn’t use various permutations when spelling his own name, although in the sonnet’s dedication where there appears to be random spellings of the words ‘onlie, insuing, eternitie and happinesse,’ they are in fact spelt this way for good reason, not just to create curiosity. Validation of the Dedication to Henry Wriothesley. We can validate the fact that the sonnets are dedicated to Henry Wriothesley because of information contained within the dedication, a truth confirmed because this fact is ‘three times’ endorsed. The first endorsement is quite simply found. If one counts the amount of letters in the dedication the sum total equals 144. If we then move to line 144 of Shakespeare’s poem ‘The Rape of Lucrece’ we find Henry Wriothesley’s motto ‘One for all, all for one’ embedded within the line ‘That one for all or all for one we gage.’ The second endorsement is expressed within the phrase ‘The only begetter of these insuing sonnets Mr. W. H.’ These initials being Henry Wriothesley’s reversed – while there are good reasons why this transposition was necessary, which I shall come to later. The third endorsement is found within an encryption of the dedication, making it more complicated than the previous two – though shortly I shall describe it in detail. Meanwhile it should not be forgotten that both of Shakespeare’s long narrative poems ‘Venus & Adonis’ 1593 and ‘The Rape of Lucrece’ published the following year – were both dedicated to Wriothesley, so including the sonnets we have a total of ‘three works’ dedicated to him. The Geometry of the Dedication. In terms of graphics – the author requires us to see the dedication as three inverted triangles, or three upside-down pyramid if you like (as already seen in the illustration above.) The top triangle composed of 6 lines, the middle triangle composed of 2 lines & the bottom triangle composed of 4 lines. Please now retain this 6 – 2 – 4 code in your mind – while I continue. As I have said there are a total of 30 words – divided by a line of two, therefore using basic mathematics, divide 30 x 2 = 15. This next part is quite fun – for which you will need a piece of paper and a pen or pencil. I believe you will find it quite rewarding if you concede to this request, for not only is it an interesting exercise but it will also help you begin to understand the almost otherworldly intelligence behind the cipher, although the section I am interested in sharing with you is only the tip of the iceberg. Now write out every letter within the dedication in lines of 15, each letter falling beneath the one in the row above until you have completed a grid of six rows then you can stop. If you have completed the task correctly in the seventh vertical line from the second letter down you will read the name HENRY. If you now complete the same task as you did before but this time creating a grid of 18 rows while exhausting all the letters, in a combination of letters, in three different vertical rows you will be able to read the dedicatee’s surname. Starting in the second vertical row the bottom two letters read – WR – then in the eleventh row three spaces from the bottom begin the letters – IOTH – then in the previous row reading from the top are the concluding letters – ESLEY – spelling in full the name WRIOTHESLEY. As has already been stated Shake-speare’s two previous long narrative poems were both dedicated to Wriothesley so it should come as little surprise to learn that the mysterious dedicatee ‘Mr. W.H.’ of Shake-speare’s third and final dedication is also Henry Wriothesley. Many commentators have mentioned that Shake-speare would not have dedicated his Sonnets to a lord by calling him Mr. but there is a good reason for this. Naturally during the major construction of the sonnets Henry Wriothesley maintained his title as the 3rd Earl of Southampton but at their completion became plain ‘Mr.’ because he had been found guilty of treason by the crown (in respect of the part he played in the Essex rebellion) and upon the verdict all his titles and lands were forfeited, confiscated by the crown at a time he became officially known as ‘the late earl.’ Therefore it can be seen that everything our author was personally responsible for publishing, was dedicated to Henry Wriothesley thereby illustrating his great importance, which leads me on to a pronouncement, a gesture unfamiliar to my normal sense of humility, which is this:

Having seen a good number of Elizabethan and Jacobean literary dedications I am obliged to say that there are no others quite like this – its format is unique. Which does prompt the question why? If we look a little closer, we see that every word is divided by a full-stop, the reason being that the author wishes us to count the words – which amount to thirty. The irregularities in spelling are another intriguing facet; these though are not eccentricities, but quite deliberate, for without these unorthodox spellings the cipher would not work. Though some would have us believe differently a polymath like Shake-speare didn’t use various permutations when spelling his own name, although in the sonnet’s dedication where there appears to be random spellings of the words ‘onlie, insuing, eternitie and happinesse,’ they are in fact spelt this way for good reason, not just to create curiosity. Validation of the Dedication to Henry Wriothesley. We can validate the fact that the sonnets are dedicated to Henry Wriothesley because of information contained within the dedication, a truth confirmed because this fact is ‘three times’ endorsed. The first endorsement is quite simply found. If one counts the amount of letters in the dedication the sum total equals 144. If we then move to line 144 of Shakespeare’s poem ‘The Rape of Lucrece’ we find Henry Wriothesley’s motto ‘One for all, all for one’ embedded within the line ‘That one for all or all for one we gage.’ The second endorsement is expressed within the phrase ‘The only begetter of these insuing sonnets Mr. W. H.’ These initials being Henry Wriothesley’s reversed – while there are good reasons why this transposition was necessary, which I shall come to later. The third endorsement is found within an encryption of the dedication, making it more complicated than the previous two – though shortly I shall describe it in detail. Meanwhile it should not be forgotten that both of Shakespeare’s long narrative poems ‘Venus & Adonis’ 1593 and ‘The Rape of Lucrece’ published the following year – were both dedicated to Wriothesley, so including the sonnets we have a total of ‘three works’ dedicated to him. The Geometry of the Dedication. In terms of graphics – the author requires us to see the dedication as three inverted triangles, or three upside-down pyramid if you like (as already seen in the illustration above.) The top triangle composed of 6 lines, the middle triangle composed of 2 lines & the bottom triangle composed of 4 lines. Please now retain this 6 – 2 – 4 code in your mind – while I continue. As I have said there are a total of 30 words – divided by a line of two, therefore using basic mathematics, divide 30 x 2 = 15. This next part is quite fun – for which you will need a piece of paper and a pen or pencil. I believe you will find it quite rewarding if you concede to this request, for not only is it an interesting exercise but it will also help you begin to understand the almost otherworldly intelligence behind the cipher, although the section I am interested in sharing with you is only the tip of the iceberg. Now write out every letter within the dedication in lines of 15, each letter falling beneath the one in the row above until you have completed a grid of six rows then you can stop. If you have completed the task correctly in the seventh vertical line from the second letter down you will read the name HENRY. If you now complete the same task as you did before but this time creating a grid of 18 rows while exhausting all the letters, in a combination of letters, in three different vertical rows you will be able to read the dedicatee’s surname. Starting in the second vertical row the bottom two letters read – WR – then in the eleventh row three spaces from the bottom begin the letters – IOTH – then in the previous row reading from the top are the concluding letters – ESLEY – spelling in full the name WRIOTHESLEY. As has already been stated Shake-speare’s two previous long narrative poems were both dedicated to Wriothesley so it should come as little surprise to learn that the mysterious dedicatee ‘Mr. W.H.’ of Shake-speare’s third and final dedication is also Henry Wriothesley. Many commentators have mentioned that Shake-speare would not have dedicated his Sonnets to a lord by calling him Mr. but there is a good reason for this. Naturally during the major construction of the sonnets Henry Wriothesley maintained his title as the 3rd Earl of Southampton but at their completion became plain ‘Mr.’ because he had been found guilty of treason by the crown (in respect of the part he played in the Essex rebellion) and upon the verdict all his titles and lands were forfeited, confiscated by the crown at a time he became officially known as ‘the late earl.’ Therefore it can be seen that everything our author was personally responsible for publishing, was dedicated to Henry Wriothesley thereby illustrating his great importance, which leads me on to a pronouncement, a gesture unfamiliar to my normal sense of humility, which is this:

If you do not know who Henry Wriothesley is – then you do not know who William Shake-speare is!

– The Importance of Mottos in Shake-speare –

As already seen, the most important people to Shakes-speare can be identified within his literature by their mottos. The character Polonius ‘The unseen good old man’ who is slain behind the Arras in Hamlet, is a parody of Lord Burghley, Queen Elizabeth’s first minister. We know this because in the first quarto of the play this character is called ‘Corambis’ a name derived from Burley’s motto ‘Cor unam via una’ which translates to ‘One heart one way.’ but corrupted by our author to ‘Corambis’ meaning ‘Two Hearted!’ Something that was seen by the authorities as an unnecessary defamation of character, predictably causing the censors to flex their muscles, while in the process rather spoiling our author’s fun, because the name ‘Corambis’ was ‘corrected’ before the second quarto was printed – when it became Polonius.

Lord Burghley riding a mule, beneath the coat of arms inscribed on the tree his motto Cor unam via una.

Lord Burghley riding a mule, beneath the coat of arms inscribed on the tree his motto Cor unam via una.

– The Tudor-Trinity – their motto’s –

Now here’s a tasty morsel! Because if we look at line five of (S76) we get two mottos side by side – just as if they were kith and kin. (S76) Why write I still all one, ever the same. Here we have Elizabeth’s motto (Semper Eadem) ‘ever the same’ immediately preceded by Wriothesley’s motto, here contracted to ‘all one.’ Now if you think this is farfetched – it isn’t. Henry Wriothesley’s motto ‘One for all, all for one’ in many guises pervades the sonnets, here are some of the variations the author uses, ‘All in one,’ ‘One of one,’ ‘All the all,’ ‘All or all.’ The fourth line that follows, from one of Shake-speare’s most harmonious sonnets illustrates this point. (S8) Mark how one string, sweet husband to another, Strikes each in each by mutual ordering, Resembling sire and child and happy mother, Who, all in one, one pleasing note doth sing. I fervently believe that here the author refers to himself as the sire and that the child is Wriothesley and the ‘happy mother’ our virgin Queen Elizabeth I. Therefore our Tudor-Trinity can be seen concisely as ‘Father, Prince, Queen.’ According to Charles Beauclerk writer of Shakespeare’s Lost Kingdom, ‘happy’ in this sense ‘designates the special grace and felicity that attends the possession of royal blood,’ which also nicely explains the meaning of the words ‘all happinesse’ in the third line of the sonnets dedication. If we now return to the dedication using our 6 – 2 – 4 code while taking heed of the full stops, selecting words 6 – 2 – 4 in sequence (which literally means isolating words 6 – 8 – 12 – 18 & 20) we find the first part of an encrypted message, reading ‘These Sonnets All By Ever’ (These sonnets all by E. Ver) The name E.Ver being an abbreviation for Edward de Vere the 17th Earl of Oxford the ‘true author’ of the works whose name is also represented by the code 6 – 2 – 4 these being the amount of letters in the name – Edward de Vere. Sometime following his ‘grand tour’ of Europe in 1575/76 Edward de Vere chose the witty name William Shake-speare as his pen-name, it relating to the Greek goddess Pallas Athena goddess of War and wisdom, literature, drama and poetry. The name Shake-speare simply refers to her birth, for myth informs us that she was born in warlike mode from the forehead of Zeus, bedecked in golden armour and shaking a spear – which is why the pseudo-name Shake-speare is a perfect witticism for a playwright and poet. The hyphen that divides the name ‘Shake-speare’ found on the title page of the sonnets is how the author intended it to be written, thereby accentuating the idea of a man shaking his spear at the world, while also stressing the fact that this name is part of ‘his invention.’

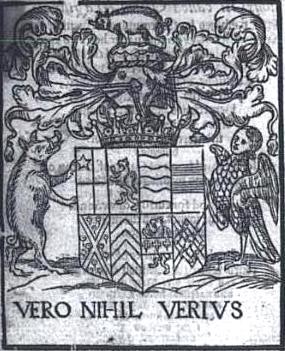

– The De Vere Double ‘ V V ‘ Insignia –

We have already seen our author’s fondness for contractions, the de Vere double ‘ V V ‘ insignia is a further representation of this tendency by our author, it represents the de Vere family motto ‘Vero Nihil Verius’ which translates to ‘Nothing truer than truth.’ While it is not surprising the word ‘true’ is the word he uses most frequently to identify himself, a tendency elaborated upon in the following sonnet.

(S.82) What strained touches rhetoric can lend, Thou, truly fair, wert truly sympathized, In true plain words by a true-telling friend. Here within two lines our author manages to use derivations of the word ‘true’ four times! The de Vere family crest is the blue boar (an animal intimately associated with Shake-speare – the beast that deprived Adonis of his breath) which can be seen below surmounting the de Vere coat of arms. Generations of de Vere knights on top of their helmets wore coronets surmounted by blue boars; such an example once belonging to the 13th Earl of Oxford can be seen in The Bargello Museum Florence.

This may be a slightly fanciful notion, but if we consider the Bath sonnets 153 & 154 they being epigrams – as separate entities – to the main body of work. Then the dead centre of the remaining 152 sonnets is line 7 of sonnet 76, which reads: ‘That every word doth almost tell my name.’ Now obviously I don’t personally waste any time wondering what that name is, because I know full well! It is a name found easily by looking at the following illustration which is the dedication to Venus & Adonis.

Firstly it is interestingly that both these ‘dedication’ pages are signed William Shakespeare and on both occasions the ‘W’ used for William is a conventional one. While on both occasions our author choses the double ‘ V V ‘ insignia for VVriothesley’s name – thereby associating him with the house of de Vere. In the dedication to Venus & Adonis it is noticeable in the first line by the acute w’s in the words ‘know’ & ‘how’ that conventional w’s are available to the compositor, while in the penultimate line, that begins ‘may always answer your own wish’ double u’s with decorative swashes are preferred. The purpose of this preference is that within the word ‘answere’ we can more easily see the name ‘Vere’. For those of you I hear scoffing – well! You may be interested to know that in the dedication to ‘Lucrece’ we have exactly the same thing going on, where four lines from its conclusion we again find the name ‘Vere’.

There is of course no way on earth that on two occasions in such prominent positions the name ‘Vere’ could appear coincidentally. It has been put there purposefully at the command of our author, to let us know who the true author of these works is. Confirming my beliefs about the double V V insignia, in a letter printed in a pamphlet published by John Lyly (Edward de Vere’s private secretary) we see Oxford sign himself off ‘Yours at an hours warning – Double V.’

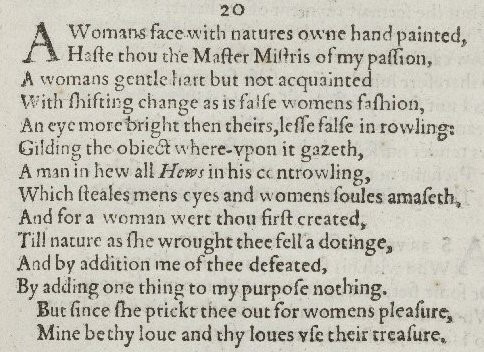

Not surprisingly with his name being E.Vere he also had a penchant for words that incorporate it, such as never, ever and every, the most famous expression of this being the prologue to Troilus and Cressida which begins ‘A Never Writer to an Ever Reader, News.’ Words that couldn’t possibly have a simpler translation, ‘An E Vere writer to an E Vere reader.’ Here follows a further illustration of this tendency. (S116) O no, it is an ever-fixèd mark, That looks on tempests and is never shaken, It is the star to every wand’ring bark…… If this be error and upon me proved, I never writ, nor no man ever loved. There is a precedent for the manner in which ‘Oxford’ expresses himself here, in one of his earlier works the ‘Echo Verses’ while verifying the fact that what we see above is not mere coincidence. Quite conveniently Oxford’s surname is a marsupial of the word ‘verses’ which is how the first syllable should be pronounced, to rhyme with hair, dare, fair etc. Equally they are called the ‘Echo Verses’ because the last word in every line is repeated with the rhyming word Vere, here follows an extract. Oh Heavens! Who was the first that bred in me this fever ? Vere Who was the first that gave the wound whose fear I wear for ever ? Vere What tyrant, Cupid, to my harm usurps thy golden quiver ? Vere What wight first caught this heart and can from bondage it deliver ? Vere In the following sonnet extract I have selected, the first line seems to challenge the very notion that his royal son could be composed of the same elements as mere mortals and where the words ‘every-one’ represent the father-son nexus, words written at a time Wriothesley was incarcerated in the tower. (S53) What is your substance, whereof are you made, That millions of strange shadows on you tend? Since every one hath, every one, one shade, And you, but one, can every shadow lend. Describe Adonis, and the counterfeit, Is poorly imitated after you. Most of you will be familiar with the notion that when Elizabeth’s brow was anointed at her coronation by the Archbishop of Canterbury she became God’s representative on earth and that any issue from her body would also carry this holy glory. So if you have ever wondered why our great author’s works are prepossessed with thoughts regarding the succession of the monarchy this knowledge may help bring some rationale to those thoughts. Following Henry Wriothesley’s birth, naturally such thoughts constantly preoccupied Oxford, but while on the one hand he felt great pride in his paternity, on the other he felt great guilt being unable to legitimize his princely son, a situation day by day that became increasingly hopeless as the petty pace of life distanced Elizabeth from Oxford and Wriothesley. As a coping mechanism for the inadequacy he felt at this rejection he began to heap all his aspirations, hopes and affections on his son, with what were the beginnings of a passionate devotion – a love that gradually blossomed into something very close to, if not, obsession. My thoughts about Shake-speare’s two previous dedications to Venus & Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece are that they both display an almost unnatural level of reverence to the dedicatee (Henry Wriothesley) but as one considers the possibilities of this father/prince relationship these sentiments seem less idiosyncratic, although this reverential acclaim remains ubiquitous throughout the sonnets. Though while searching for concise words adequately describing this love, I find myself deficient, because the true nature of their relationship surely is incomprehensible to any outsider, all I can safely say is – that the tender sentiments expressed in the sonnets have certainly kindled the world’s imagination. (S17) Who will believe my verse in time to come If it were filled with your most high deserts?…… If I could write the beauty of your eyes And in fresh numbers number all your graces, The age to come would say, ‘This poet lies: Such heavenly touches ne’er touched earthly faces.’ So should my papers, yellowed with their age, Be scorned like old men of less truth than tongue, And your true rights be termed a poet’s rage, And stretchèd meter of an antique song. (S18) Sometimes too hot the eye of heaven shines And often is his gold complexion dimmed. (Even the sun is eclipsed by the radiance of Wriothesley) (S19) Talking of swift footed time:- O, carve not with thy hours my love’s fair brow, Nor draw no lines there with thine antique pen. Him in thy course untainted do allow, For beauty’s pattern to succeeding men: (S20) An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling, Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth. A man in hue, all hues in his controlling, Which steals men’s eyes and women’s souls amazeth. (S37) For whether beauty, birth or wealth or wit. Or any of these all or all or more, Entitled in thy parts do crownèd sit, I make my love engrafted to this store. (S87) Thus have I had thee as a dream doth flatter, In sleep a king, but waking no such matter. (S98) Tudor Colours:- Nor did I wonder at the lily’s white, Nor praise the deep vermilion of the rose. They were but sweet, but figures of delight, Drawn after you, you pattern of all those. (S99) Of royal (purple) blood:- The forward violet thus did I chide: Sweet thief, whence didst thou steel thy sweet that smells If not from my love’s breath? The purple pride Which on thy soft cheek for complexion dwells In my love’s veins thou has too grossly dyed. (S114) Such cherubins as your sweet self resemble. (S110) A god in love, to whom I am confined.

There was only one person in Elizabethan England that commissioned more portraits of themselves than Henry Wriothesley – and that was Queen Elizabeth herself.

There was only one person in Elizabethan England that commissioned more portraits of themselves than Henry Wriothesley – and that was Queen Elizabeth herself.

– The Fair Youth –

(Illustrated above) Shake-speare’s ‘Fair youth’ Henry Wriothesley as a somewhat narcissistic teenager. He has plucked eyebrows possibly in imitation of his mother who was known to pluck hers, along with her hairline to increase the dimension of her forehead; his also appears to be rather high so he possibly copied her in that as well. He also wears a coral coloured earing in the shape of an ‘O’ tied in a love knot, his hand upon his lustrous-locks which he liked to wear long as he considered his hair a badge of honour. Oxford far from turning a blind eye to these vanities describes his androgynous son most skillfully in sonnet twenty, while he may well have been referring to Elizabeth when using the word ‘nature’ as in her lifetime she was often associated with it. There can though be no doubt, that although Wriothesley is fair (in terms of beauty not colouring) his equipment in fact is male, for the third line states he is without ‘quaint’ while confirming in the penultimate line ‘Nature pricked the out for woman’s pleasure.’ But be mindful, in Shake-speare’s time the word ‘passion’ had a more religious connotation than today. (S20) A woman’s face with nature’s own hand painted Hast thou, the master-mistress of my passion, A woman’s gentle heart, but not acquainted While shifting change as is false woman’s fashion, An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling, Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth: A man in hue, all hues in his controlling, Which steals men’s eyes and woman’s souls amazeth, And for a woman wert thou first created, Till nature as she wrought thee fell a-doting, And by addition me of thee defeated By adding one thing to my purpose nothing. But since she pricked thee out for woman’s pleasure, Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure. One of the reasons for this article has been to elaborate upon our author’s sensitivity to words in the form of various contractions. This we see most profoundly in Sonnet 20 when looking at the original 1609 version (a facsimile below) where the word Hews (spelled hues today) in line seven is a contraction of the name Henry Wriothesley – but because of his royal DNA it is both italicised and capitalised, the only word in the sonnet highlighted in this way. There are two sonnets (above all others) fundamentally sexual in content (S20 & S151) which to my mind show where our author’s sexual preferences lay – they lay in the rather rude symbolism suggested in (S151). Whereas lines eleven and twelve in the above sonnet say to me that by nature’s addition of one thing (a prick) that this is very much just an appendage, something of no consequence to our author, for in respect of the fair youth he is ultimately ambivalent to all these sexual matters as the ‘passion’ he has for him is felt in his soul – not in his loins; because the ‘eternal summer’ of love that Wriothesley is subjected to is not of mortal composition, but ethereal, valiant, virtuous, spiritual, transcending all base earthly constraints.  A little History. In the early spring of 1574 the fact that Oxford was married to Lord Burghley’s daughter was a big problem that stood in the way of Elizabeth and Oxford’s intended betrothal. At this time it is known that on three separate occasions Elizabeth and Oxford together visited the Archbishop of Canterbury to seek his guidance, on two occasions they visited him at Lambeth Palace and on a further occasion they even went as far as the Old Palace Croydon to see him there. It is said that Wriothesley was possibly born at Havering Park (Havering-atte-Bower) a place special to Elizabeth and Oxford where they were known to have met for hunting and romantic trysts. Sometime later following Wriothesley’s birth they met again at Greenwich where it is believed the Queen most probably influenced by Burghley reneged on her promises to Oxford regarding their future and that of their princely son. Being a great poet of course also comes with a large amount of baggage – the fact that just like Prince Hamlet – Oxford’s father had been murdered didn’t really help, nor did the fact that at that time the great majority of his estates had been appropriated by the state, many of these ending up in the hands of his nemesis the Earl of Leicester, add to this the fact that the most common word used by his contemporaries to describe him was fickle and what you had was a powder-keg waiting to explode, which is exactly what happened, with Oxford using words that no man should use in front of a woman – let alone a Queen. Following this gross exchange Oxford swiftly mounted his steed and fled for his life not looking back until he reached Flanders.

A little History. In the early spring of 1574 the fact that Oxford was married to Lord Burghley’s daughter was a big problem that stood in the way of Elizabeth and Oxford’s intended betrothal. At this time it is known that on three separate occasions Elizabeth and Oxford together visited the Archbishop of Canterbury to seek his guidance, on two occasions they visited him at Lambeth Palace and on a further occasion they even went as far as the Old Palace Croydon to see him there. It is said that Wriothesley was possibly born at Havering Park (Havering-atte-Bower) a place special to Elizabeth and Oxford where they were known to have met for hunting and romantic trysts. Sometime later following Wriothesley’s birth they met again at Greenwich where it is believed the Queen most probably influenced by Burghley reneged on her promises to Oxford regarding their future and that of their princely son. Being a great poet of course also comes with a large amount of baggage – the fact that just like Prince Hamlet – Oxford’s father had been murdered didn’t really help, nor did the fact that at that time the great majority of his estates had been appropriated by the state, many of these ending up in the hands of his nemesis the Earl of Leicester, add to this the fact that the most common word used by his contemporaries to describe him was fickle and what you had was a powder-keg waiting to explode, which is exactly what happened, with Oxford using words that no man should use in front of a woman – let alone a Queen. Following this gross exchange Oxford swiftly mounted his steed and fled for his life not looking back until he reached Flanders.

– Edward de Vere the 17th Earl of Oxford – The ‘Wellbeck Portrait’ 1575 – Painted in Paris by an unknown artist. The National Portrait Gallery London

– Edward de Vere the 17th Earl of Oxford – The ‘Wellbeck Portrait’ 1575 – Painted in Paris by an unknown artist. The National Portrait Gallery London

Luckily for him Elizabeth took a conciliatory attitude to this debacle and sent one of his literary cronies Thomas Bedingfield to bring him home stressing there would be no punitive action taken by her. The Queen only went to the city of Bath once during her reign – the same year Wriothesley was born. He was born in May and she arrived there for a three day stay on August 21st 1574 (the anniversary of Wriothesley’s conception) quite naturally she was accompanied by a massive entourage, composed of hundreds of wagon’s, within which where secreted both wet-nurse and infant child. Following her travails of love with its soothing hot mineral waters Bath turned out to be an appropriate destination for Elizabeth, but it is worth remembering what a long and exhausting journey it would have been for Oxford returning from Brussels, his emotions peppered with buckshot while no doubt feeling some trepidation about how he would be received by his mistress. Now listen to how this exact scenario is described using four of the most important lines in all Shake-speare – lines important because in the first instance they describe Bath not as something you immerse yourself in – but as a place you go to, represented by the words ‘And thither hied.’ The OED definition; ‘And went quickly to that place.’

| (S153) I, sick withal, the help of bath desired, And thither hied, a sad distempered guest, But found no cure; the bath for my help lies, Where cupid got new fire my mistress eyes. | (My Improvisation.) Fed up with everything (under duress) I went to Bath – an emotional wreck Seeking salvation for my loving soul In the unfathomable depths of Elizabeth’s eyes. |

‘The Ermine Portrait’ of Queen Elizabeth I, attributed to Nicholas Hilliard, Hatfield House – Hertfordshire.

‘The Ermine Portrait’ of Queen Elizabeth I, attributed to Nicholas Hilliard, Hatfield House – Hertfordshire.

One thing that must be remembered at all times while reading the sonnets is that from the authorities perspective they were subversive and treasonous. Therefore for every libel perceived against the Crown, from the author’s point of view there had to be an alternative interpretation. This is why they seem so complex to the casual observer and why T.S. Eliot said in 1927 that they were written by a foreign man in a foreign tongue, never to be translated. Furthermore there is absolutely no doubt in my mind that having dedicated his first two published poems Venus and Adonis and Lucrece both to Henry Wriothesley our author would have been told in no uncertain terms by the authorities that a third dedication to Wriothesley would be met with extremely serious consequences, which is part of the reason Shake-speare’s sonnets are dedicated to ‘Mr W.H.’ How convenient then that Oxford and the ‘incomparable pair of brethren’ to whom the first folio was dedicated, were intimately associated with one another. Philip Herbert Earl of Montgomery married Oxford’s daughter Susan while his brother William the 3rd Earl of Pembroke was engaged to another of Oxford’s daughters Bridget in the year 1597. Consequently if the authorities had caught Oxford with these subversive works, to save his life he could have responded by saying that the sonnets were dedicated to his close friend William Herbert, ‘Mr W.H.’ Now as we further consider the history of our Tudor-Trinity, it is worth paying attention to the words of (S33) with its sun (son) pun, note how it says ‘my sun’ and not ‘the sun’ and two lines later ‘he was’ and not ‘it was.’ The first quatrain is not included for although very beautiful it is simply a eulogy by a besotted father to the golden love-god – Henry Wriothesley. Anon permit the basest clouds to ride With ugly rack on his celestial face, And from the forlorn world his visage hide, Stealing unseen to west with this disgrace; Even so my sun one early morn did shine, With all-triumphant splendour on my brow; But out, alack, he was but one hour mine, The region cloud hath masked him from me now, Yet him for this my love no whit distaineth; Suns of the world may stain when heaven’s sun staineth This is how I see it Soon the repressive ogre of Tudor England Casts its dark shadow upon our princes heavenly features, Denying his existence to the populace. While her majesty surreptitiously travels to Bath (as if nothing had happened) A proud father triumphs in the presence of a new born son, A fleeting pleasure lasting just one hour, Before obscurity is fashioned by Elizabeth Regina’s frown, And though the sun stains western sky’s at sunset, Royal sons are more permanently stained by the stigma of bastardy. ‘And the imperial votaress passed on – in maiden meditation, fancy free.’ (A Midsummer Night’s Dream.) Now to consider the first four lines of Shake-speare’s first sonnet (S1) remembering that the word ‘rose’ (ever sacred to Venus) was highlighted in the original as it is below, while throughout the sonnets, it is worth being aware that the words ‘fair’ or ‘fairest’ may be an allusion to a princely or regal state, something noticeable in the very last sonnet within the phrase ‘The fairest votary.’ From fairest creatures we desire increase, That thereby Beauty’s Rose might never die, But as the riper should by time decease, His tender heir might bear his memory: In the beginning, procreation is on the mind of our sonneteer, which he bangs on about sonnet after sonnet for quite a while (actually for seventeen sonnets.) His favorite word for describing Elizabeth is ‘Beauty,’ his second being ‘Mistress’ while ‘Nature’ is another, though there is little surprise the sonnets open with a reference to Wriothesley who Oxford saw dynastically through rose coloured spectacles as both England’s Tudor Rose or alternatively as Beauties’ Rose. The word Rose is significant because the name Wriothesley obviously spoken with a silent ‘W’ is actually pronounced ‘rose-ley,’ while the word rose can also be seen as a contraction, or more correctly (a marsupial) of the surname Wriothesley. In respect of this floral iconography there is a relevant antecedent to it, with a Meleagris Lily (snake’s-head fritillary) representing a miraculous birth, a flowering which appears at the climax of Venus & Adonis a story that is an allegory for the love affair between Elizabeth and Oxford with the flower representing Wriothesley’s birth.

Venus lamenting Adonis (line 1177) “Poor flower – this was thy father’s guise.”

Venus lamenting Adonis (line 1177) “Poor flower – this was thy father’s guise.”

While considering this story it is important to remember that Elizabeth was seventeen years older than Oxford, a fact he didn’t want to go amiss on the battlefields of literature. Therefore unlike Ovid, with an innovation to convention Shake-speare unfolds his tale of Venus as the older experienced lover who relentlessly pursues the youth Adonis, an age differential elaborated upon in verse eighty-eight of the poem where it can be seen that at this stage of these loving-shenanigans Adonis remains ‘un-plucked’ because he says, “seek not to know me.” ‘Fair queen,’ quoth he, ‘if any love you owe me, Measure my strangeness with my unripe years, Before I know myself, seek not to know me. No fisher but the ungrown fry forebears: The mellow plum doth fall, the green sticks fast, Or being early plucked is sour to taste. Our youth not persuaded by the wiles of love is more persuaded by the heroism of hunting the wild boar – a beast which towards the conclusion of the poem, charges him, depriving him of his sweet breath, it is therefore his own courage that ultimately destroys him. By this, the boy that by her side lay killed Was melted like a vapour from her sight, And in his blood that on the ground lay spilled A purple flower sprung up, chequered with white, Resembling well his pale cheeks and the blood Which in round drops upon their whiteness stood. She bows her head, the new sprung flower to smell, Comparing it to her Adonis’ breath, And says within her bosom it shall dwell, Since he himself is reft from her by death, She crops the stalk and in the breach appears Green dropping sap, which she compares to tears ‘Poor flower,’ quoth she, ‘this was thy father’s guise, Sweet issue of a more sweet-smelling sire, For every little grief to wet his eyes, To grow unto himself was his desire, And so ‘tis thine: but know, it is as good To wither in my breast as in his blood. ‘Here was thy father’s bed, here in my breast, Thou art the next of blood, and ‘tis thy right. Lo, in this hollow cradle take thy rest, My throbbing heart shall rock thee day and night. There shall not be one minute in an hour Wherein I will not kiss my sweet love’s flower.’ Thus weary of the world, away she hies And yokes her silver doves, by whose swift aid Their mistress, mounted, through the empty skies In her light chariot quickly is conveyed, Holding their course to Paphos, where their queen Means to immure herself and not be seen. Interestingly the ancient bath houses at the sanctuary of Paphos in Cyprus are in the ‘west,’ where a Queen after giving birth could immure herself (hide away) and not be seen. These two stories of Venus & Adonis and Elizabeth & Oxford are so deeply intertwined and have received so much scholarly debate I shall spend little further time examining them. Suffice to say that although Wriothesley is the flower cradled between the goddesses breasts, one can’t help but note the apt use of the word ‘wither’ which in light of history turns out to be rather prophetic, because the words ‘Thou art the next of blood, and ‘tis thy right’ obviously pertain to the succession. Now let us look a little closer at this royal flower. ‘And in his blood that on the ground lay spilled A purple flower sprung up chequered with white.’  This flower held proudly by Adonis was first recorded in literature by John Gerard in his groundbreaking book The Herbal, originally published in 1597 a book intriguingly considered a primary source for Shake-speare’s extensive botanical knowledge, while equally interesting is the fact that its foreword was written by the Earl of Oxford’s personal physician Dr. George Baker. Still even more interesting is the front-piece engraving which illustrates four people, the author John Gerard, Flemish botanist Rembert Dodoens, Lord Burghley and the Earl of Oxford who (above) is adorned in the theatrical guise of Adonis. We know this figure is the poet Adonis because he wears a wreath of bays on his head, while in his left hand he carries a husk of corn symbolising Ceres the corn Goddess. In book X of Ovid’s Metamorphoses King Cinyras and his daughter Myrra were found in an incestuous encounter, which resulted in the birth of Adonis. We also know he is Adonis because above his head he holds a Meleagris Lily the precise same flower described in Shake-speare’s poem Venus & Adonis. ‘A purple flower sprung up chequered with white,’ but how do we know Adonis and the Earl of Oxford are one and the same?

This flower held proudly by Adonis was first recorded in literature by John Gerard in his groundbreaking book The Herbal, originally published in 1597 a book intriguingly considered a primary source for Shake-speare’s extensive botanical knowledge, while equally interesting is the fact that its foreword was written by the Earl of Oxford’s personal physician Dr. George Baker. Still even more interesting is the front-piece engraving which illustrates four people, the author John Gerard, Flemish botanist Rembert Dodoens, Lord Burghley and the Earl of Oxford who (above) is adorned in the theatrical guise of Adonis. We know this figure is the poet Adonis because he wears a wreath of bays on his head, while in his left hand he carries a husk of corn symbolising Ceres the corn Goddess. In book X of Ovid’s Metamorphoses King Cinyras and his daughter Myrra were found in an incestuous encounter, which resulted in the birth of Adonis. We also know he is Adonis because above his head he holds a Meleagris Lily the precise same flower described in Shake-speare’s poem Venus & Adonis. ‘A purple flower sprung up chequered with white,’ but how do we know Adonis and the Earl of Oxford are one and the same?

– Oxford at Cecil House –

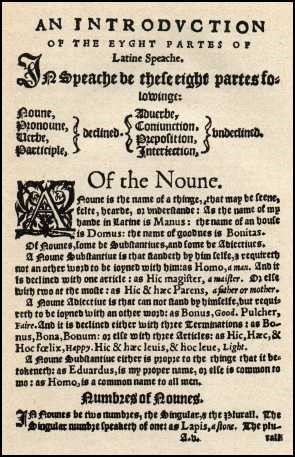

Child of Letters – Man of Letters, Oxford was both, his education began at the age of four but never really stopped – an education a grateful world has become a beneficiary of, defined by an erudition that leaps from every page of Shake-speare into our laps, so what I want to look at more carefully is his relationship with what has been described as a humanist-salon the place where from the age of twelve the second phase of his education began, Cecil-House. If one examines the front-piece engraving from the 1597 edition of The Herbal (below), then to the right of where it says ‘Imprinted at London by John Norton’ there can be seen the image of Adonis. Below this centrally there is a cartouche within which there is an image of the garden at Cecil House, the building itself identifiable because it was known to be four stories high with turrets at each corner. B.M.Ward Oxford’s first biographer said that Burghley liked to ‘Imbue his son’s and the royal wards under his charge with his own keenness of horticulture.’  As Oxford was born into the most distinguished earldom in England it was hardly surprising that he developed a keen interest in ancient history, an interest that naturally went hand in hand with literature. One of the great attractions for Oxford at Cecil House would of course have been the library, though he had been particularly fortunate that even before his arrival at the Inns of Courts and Oxbridge that he had been introduced to two of the greatest libraries in England. Sir Thomas Smith who was Oxford’s senior tutor for eight years before he arrived at Cecil House had a vast library with volumes in many languages, including Italian, Latin, Greek, French and English etc. all languages that Oxford studied and became fluent in. While an ancillary fact worth bearing in mind is that in the year 1582 the university library at Cambridge had a total of 451 manuscripts and books, whereas it is believed that Burghley’s library at Cecil house had over 1700 volumes. As it transpired two books in particular in Cecil’s library would have considerable influence on both Oxford’s travels and his career, the first of these in Latin was Homer’s Odyssey; the other in Italian was Virgil’s The Aeneid. J.A. van Dorsten discussing the intellectual climate at Cecil House said that as a meeting place for the learned it had no parallel in early Elizabethan England. Its tutor’s naturally were of the very highest caliber. Laurence Nowell the Anglo-Saxon scholar and antiquarian was one of these, while his name today is associated with the “Nowell Codex” as in the same year 1563 (the year in which he was known to be instructing Oxford) he signed his name within this volume of manuscripts containing the only known copy of Beowulf. Let me quote from Mark Anderson’s Book Shakespeare by another name, ‘Beowulf was as inaccessible as the crown jewels to anyone outside Cecil House’ ………. ‘Beowulf and the original Hamlet myth (Amleth) are cousins from the same family of Scandinavian folklore. Shake-speare uses both as sources for Hamlet. Once Hamlet kills his uncle Claudius, Shake-speare stops following ‘Amleth’ and starts following Beowulf. It is Beowulf who fights the mortal duel with poison and sword; it is Beowulf who turns to his loyal comrade (Wiglaf in Beowulf; Horatio in Hamlet) to recite a dying appeal to carry his name and cause forward; and it is Beowulf that carries on after its hero’s death to dramatize a succession struggle for the throne bought on by an invading foreign nation.’ Although consensus of opinion is a great rarity in respect of the Shakespeare authorship debate, there is general agreement of our author’s greatest non biblical influence – the Roman poet Ovid. Arthur Golding who was Oxford’s maternal uncle and a known employee of Cecil’s, worked as a tutor to Oxford at Cecil House, while it is believed simultaneously translating Ovid’s Metamorphoses from the Latin. Now, whether it represents some aggrandizement of thought or not, the idea has been advocated by a number of people that Oxford was doing a bit more than studying under Golding and that he was actively engaged with the translation itself. The finished article is very well thought of in literary circles, the poet Ezra Pound announcing it to be ‘the most beautiful book in the English language.’ As Anderson says ‘Shake-speare quotes from every one of the Metamorphoses fifteen books, and there is hardly a single Shake-speare play or poem that does not owe character, language, or plot to Ovidian mythology.’ Also worth a mention is the fact that in 1564 Golding dedicated his translation of Justin’s Abridgement of the Histories of Trogus Pompeius to his nephew, the first of 28 books dedicated to Oxford during his lifetime. The relevant question that immediately springs to mind in respect of this fact is – how many books in Stratford-William’s lifetime were dedicated to him; anyone know the answer to that? On the 5th August 1564 Oxford received from the Queen at St John’s College Cambridge a Bachelor of Arts degree, while two years later in a similar ceremony this time at Oxford he received from Elizabeth an M.A. degree. As no formal Elizabethan education was really complete without a degree in law, Oxford in February 1567 matriculated at Gray’s Inn, and as these Inns of Court were less than a mile from Cecil House Oxford retained his lodgings while he studied there. In respect of the previously mentioned, John Gerard’s Herbal, the theory has been expressed that as languages were one of the subjects that Oxford excelled in, that he had helped Gerard with translations from the Latin and Greek, which is why he appears as Adonis in the front-piece engraving of the 1597 edition. Out of respect for Oxford and by way of a thank you, the mask of Adonis that Oxford inhabits is Gerard’s way of including him in ‘the credits,’ in appreciation of his involved with the compilation of the book.

As Oxford was born into the most distinguished earldom in England it was hardly surprising that he developed a keen interest in ancient history, an interest that naturally went hand in hand with literature. One of the great attractions for Oxford at Cecil House would of course have been the library, though he had been particularly fortunate that even before his arrival at the Inns of Courts and Oxbridge that he had been introduced to two of the greatest libraries in England. Sir Thomas Smith who was Oxford’s senior tutor for eight years before he arrived at Cecil House had a vast library with volumes in many languages, including Italian, Latin, Greek, French and English etc. all languages that Oxford studied and became fluent in. While an ancillary fact worth bearing in mind is that in the year 1582 the university library at Cambridge had a total of 451 manuscripts and books, whereas it is believed that Burghley’s library at Cecil house had over 1700 volumes. As it transpired two books in particular in Cecil’s library would have considerable influence on both Oxford’s travels and his career, the first of these in Latin was Homer’s Odyssey; the other in Italian was Virgil’s The Aeneid. J.A. van Dorsten discussing the intellectual climate at Cecil House said that as a meeting place for the learned it had no parallel in early Elizabethan England. Its tutor’s naturally were of the very highest caliber. Laurence Nowell the Anglo-Saxon scholar and antiquarian was one of these, while his name today is associated with the “Nowell Codex” as in the same year 1563 (the year in which he was known to be instructing Oxford) he signed his name within this volume of manuscripts containing the only known copy of Beowulf. Let me quote from Mark Anderson’s Book Shakespeare by another name, ‘Beowulf was as inaccessible as the crown jewels to anyone outside Cecil House’ ………. ‘Beowulf and the original Hamlet myth (Amleth) are cousins from the same family of Scandinavian folklore. Shake-speare uses both as sources for Hamlet. Once Hamlet kills his uncle Claudius, Shake-speare stops following ‘Amleth’ and starts following Beowulf. It is Beowulf who fights the mortal duel with poison and sword; it is Beowulf who turns to his loyal comrade (Wiglaf in Beowulf; Horatio in Hamlet) to recite a dying appeal to carry his name and cause forward; and it is Beowulf that carries on after its hero’s death to dramatize a succession struggle for the throne bought on by an invading foreign nation.’ Although consensus of opinion is a great rarity in respect of the Shakespeare authorship debate, there is general agreement of our author’s greatest non biblical influence – the Roman poet Ovid. Arthur Golding who was Oxford’s maternal uncle and a known employee of Cecil’s, worked as a tutor to Oxford at Cecil House, while it is believed simultaneously translating Ovid’s Metamorphoses from the Latin. Now, whether it represents some aggrandizement of thought or not, the idea has been advocated by a number of people that Oxford was doing a bit more than studying under Golding and that he was actively engaged with the translation itself. The finished article is very well thought of in literary circles, the poet Ezra Pound announcing it to be ‘the most beautiful book in the English language.’ As Anderson says ‘Shake-speare quotes from every one of the Metamorphoses fifteen books, and there is hardly a single Shake-speare play or poem that does not owe character, language, or plot to Ovidian mythology.’ Also worth a mention is the fact that in 1564 Golding dedicated his translation of Justin’s Abridgement of the Histories of Trogus Pompeius to his nephew, the first of 28 books dedicated to Oxford during his lifetime. The relevant question that immediately springs to mind in respect of this fact is – how many books in Stratford-William’s lifetime were dedicated to him; anyone know the answer to that? On the 5th August 1564 Oxford received from the Queen at St John’s College Cambridge a Bachelor of Arts degree, while two years later in a similar ceremony this time at Oxford he received from Elizabeth an M.A. degree. As no formal Elizabethan education was really complete without a degree in law, Oxford in February 1567 matriculated at Gray’s Inn, and as these Inns of Court were less than a mile from Cecil House Oxford retained his lodgings while he studied there. In respect of the previously mentioned, John Gerard’s Herbal, the theory has been expressed that as languages were one of the subjects that Oxford excelled in, that he had helped Gerard with translations from the Latin and Greek, which is why he appears as Adonis in the front-piece engraving of the 1597 edition. Out of respect for Oxford and by way of a thank you, the mask of Adonis that Oxford inhabits is Gerard’s way of including him in ‘the credits,’ in appreciation of his involved with the compilation of the book.

– The Darling Buds of May –

Returning to our Rose Wriothesley it is surely worth mentioning how often he is referred to as ‘bud’ as in ‘The darling buds of May,’ because that is exactly what he was ‘A darling bud of May,’ his true birthday being the 20th May 1574 a date Shake-speare ensured was commemorated by the announcement of the publication of his sonnets in the stationer’s register, a posthumous event that took place on that very day – the 20th May 1609. Now to justify the said date (the 20th May as Wriothesley’s birthday) as collaborative evidence I cite our author’s love of irony, because in the merry month of May in the year 1573 (at a time Elizabeth & Oxford were very close) three of his men, John Hannam, Denny the Frenchman and Danny Wilkins at a place called ‘Gads Hill’ between Gravesend and Rochester in the county of Kent robbed two of Lord Burghley’s men. Now do we think our national playwright would let this spectacle of insubordinate behavior – this cache of theatrical material go to waste – without sharing it with the wider world? Thereby forsaking an incident in which highwaymen discharged their muskets at the Lord Treasure’s men – of course not! So in the early scenes of Henry IV, Part I, we have a retelling of this amusing tale where Falstaff, Bardolph and Peto rob two employees of the crown on their way to Canterbury and eventually are indicted for it, a robbery described as taking place on the ’20th May’ last past, in the fourteenth year of the reign of our sovereign Lord king Henry IV. Now as remarked upon by the writer Richard Malim in his book The Earl of Oxford and the Making of Shakespeare, there was no 20th May in the fourteenth year of Henry IV’s reign because he died on March 20, 1413. The irony here is that although the Tudor-state liked to cast a blind eye towards the 20th May, it didn’t stop our wily poet alluding to Wriothesley’s birthday in this celebratory manner in one of his earliest history plays. When wert thou born, Desire? In pride and pomp of May. By whom, sweet boy, wert thou begot By fond conceit men say. ( E.O.) Let me now proceed by saying a few words about the much maligned Edward de Vere who wasn’t just any old Earl but ‘Lord Great Chamberlain’ the highest ranking Earl in the kingdom, whose ceremonial duties included not only being canopy bearer, but also water bearer to the monarch. (S125) Were’t aught to me I bore the canopy. (S109) So that myself bring water for my stain. Beyond these duties according to Encyclopedia Britannica the De Vere family were further honoured being titled ‘Everys’ a courtesy which gave them the right at a banquet to wash the monarch’s hands before and after a feast, a privilege Oxford is known to have carried out at the coronation of James I. While from the familiar guise of poetry (the noted weed) – secrets slowly revealed themselves. (S76) Why write I still all one, ever the same, And keep invention in a noted weed, That ‘every’ word doth almost tell my name, Showing their birth and where they did proceed? Here again we see our Tudor-Trinity but if this is written by Stratford-William how can the words “every word doth almost tell my name” possibly make sense? But as we now know better, being written by Oxford, ‘every’ word makes perfect sense, by not only describing himself as an ‘Every’ but also by invoking his favorite subject the succession of the monarchy ‘showing their birth and where they did proceed or more ominously in Wriothesley’s case, the place he failed to proceed to – the throne! Shakespeare’s sonnet 105 is possibly the most obsessional of all and it can easily be seen how ‘experts’ can be lulled into believing that its major theme is about the Holy Trinity when of course it is about the Tudor-Trinity. This fact is irrefutable to my mind because in the fourth line we have a contraction of Henry Writhoseley’s moto, in this case the words ‘one of one.’ Obsession can also be seen in the repetition of detail because ‘all alike’ line three, and ‘one thing’ line eight are also Wriothesley references. These misapprehensions often made by academia are understandable partially because of the first two lines which do not relate to a conventional Godhead but underline the vaulted status conferred by our author on Wriothesley – an infatuation that he seems to be feeling self-conscious about, although, while being a true renaissance man he is not only poetical but also musical, a fact that can be substantiated because we know from (S128) that he wrote music Queen Elizabeth played. While it should not be forgotten that the literal meaning of the word sonnet is ‘little-song’ so no doubt he wrote songs for Wriothesley too, while praises to him are exactly what the sonnets are. (S105) Let not my love be called idolatry, Nor my belovèd as an idol show, Since all alike my songs and praises be To one, of one, still such and ever so, Kind is my love today, tomorrow kind, Still constant in a wondrous excellence, Therefore my verse to constancy confined, One thing expressing, leaves out difference, ‘Fair, kind and true’ is all my argument, ‘Fair, kind and true’ varying to other words, And in this change is my invention spent, Three themes in one , which wondrous scope affords. Fair, kind and true have often lived alone, Which three till now never kept seat in one. Here our author seeks to bludgeon us into submission with repetition of the same ‘theme’ expressed in ‘The Bath Sonnets’ and ‘The Phoenix and the Turtle’ although in this particular instance Elizabeth and Wriothesley become interchangeable. The ‘fair’ youth switches to ‘kind’ before becoming ‘constant’ an attribute normally attached to Elizabeth, while she is seen to be ‘fair’ once more. In my eyes there is a romanticism in the way our author sees the Tudor-Trinity for although the Queen has clearly wronged him, he is prepared to ‘leave out’ these ‘differences’ so in Heaven and on Earth they appear as constant, wondrous spirits. Where this sonnet proves itself to be a revelation though, is of course in what I have already been discussing, the fact that ‘Fair, kind and true’ are individuals, who are ‘all my argument’ while in Oxford’s invention they ‘vary’ (metamorphose) to other words. Lamentably though, through our author’s eyes ‘they have often lived alone,’ and ‘never kept seat in one’ (shared the throne together). This cosy dream of Oxford’s of sharing the throne with Elizabeth and Wriothesley was of course in reality impossible, what with Lord Burghley being Elizabeth’s chief advisor and with Burghley already having presented Oxford a £15,000 dowry to marry his daughter. One of course cannot say to what degree Oxford may have been motivated by upward-mobility, but it could be seen as ironic, having spent the majority of his life dreaming of Wrothesley as King Henry IX, if ultimately it is he that posterity honours with a halo, be it triangular or not – though lamentably I must say this does seem a long way off. Now, revisiting our sonnets once again we can see how they are an amalgam of three fundamental parts. Part one comprising 1 – 126 known as ‘The Fair Youth’ series, part two comprising 127 – 152 known as ‘The Dark Lady’ series, and part three 153 – 154 known as the ‘Bath Sonnets.’ Where confusion reigns is that although for the greater part ‘The Dark Lady’ series represents the Queen she is only viewed this way because of her tenebrous attitude towards the fair youth. Now very briefly I shall return to our triangular halo – because another reason it is apposite is because the sonnet structure itself also takes the form of a triangle.

1 ———————————————————- 126 The Fair Youth Series 127——————————– 152 The Dark Lady Series 153 – 154 Bath

Princess Elizabeth whose hair when queen created sunbeams so beguiling our poet was prepared to die!

The colours of the marigold were an allusion to Elisabeth’s hair and her flower the marigold was commented upon by Oxford’s secretary John Lyly who said “She useth the marigold for her flower, which at the rising of the sunne openeth his leaves, and at the setting shutteth them.” It was therefore ultimately Elizabeth’s gloomy negative attitude to Wriothesley that saw her incriminated by Shake-speare as the dark lady – she was after all a mother who saw her own son committed to the tower, an act provoking Oxford to describe him as ‘a Jewell hung in ghastly night.’ (S27) As for Elizabeth’s Father he was renowned for his Phoebus complexion something that both she and her half-sister Mary inherited from him, while it is worth remembering that Elizabeth’s mother Ann Boleyn had very dark hair. Little wonder then that Henry Wriothesley relished the inheritance of auburn hair, something in his day he was famous for, wearing it nearly down to his waist as a badge of honour for all to see.

Colour co-ordinated Henry VIII, Princess Elizabeth’s Father.

(S25) (The Earls Essex & Southampton) Great princes’ favorites their fair leaves spread But as the marigold at the sun’s eye, And in themselves their pride lies burièd, For at a ‘frown’ they in their glory die. As the writer Hank Whittemore says in his immense work ‘The Monument‘ Her Majesty’s imperial viewpoint determined everything; her favour was a beacon of light upon her subjects, while her ‘frown’ was a dark cloud casting it’s a shadow upon the world. ‘The Dark Lady’ series itself starts sermon like as if invoking a new testament, a new order, speaking of a world that was formerly fair – but latterly racked with darkness.

| (S127) In the old age black was not counted fair Or if it were, it bore not beauty’s name But now is black beauty’ successive heir And beauty slandered by a bastard shame. | (My interpretation) In times past, black was not considered fair (Royal) Or if it were, it bore not Elizabeth’s name of Tudor But now as he (Wriothesley) is her successive heir By association she is slandered by his illegitimacy. |

(S131) In nothing art thou black save in thy deeds. (S132) Then will I swear beauty herself is black.

– The Bath Sonnets – – The Bath Sonnets – |

|

|

(S153) Lines 1 – 14. Cupid laid by his brand and fell asleep, A maid of Dyans this advantage found, And his love-kindling fire did quickly steep In a cold valley-fountain of that ground, Which borrowed from this holy fire of love A dateless lively heat, still to endure, And grew a seething bath, which yet men prove Against strange maladies a sovereign cure, But at my mistress’ eye loves brand new-fired, The boy for trial needs would touch my breast. I, sick withal, the help of bath desired, And thither hied, a sad distempered guest, But found no cure; the bath for my help lies Where Cupid got new fire – my mistress’ eyes. |

(S154) Lines 15 – 28 The little Love-God lying once asleep Laid by his side his heart-inflaming brand, While many Nymphs that vowed chased life to keep Came tripping by, but in her maiden hand The fairest votary took up that fire Which many Legions of true hearts had warmed And so the General of hot desire Was, sleeping, by a Virgin hand disarmed. This brand she quenched in a cool Well by, Which from love’s fire took heat perpetual, Growing a bath and healthful remedy For men diseased; but I, my Mistress’ thrall, Came there for cure, and this by that I prove: Love’s fire heats water, water cools not love. |

To clarify what I meant when I said at the beginning of this article that Shake-speare’s sonnets were his opus No.1, what I believe is that if he were told he could save only one work for posterity – this would be the one he would save, regarding it as his most important in terms of what he wanted the world to know about his life and time on earth. One can then deduce how important the Bath sonnets are, being epigrams to his most important work. An importance underlined as fundamentally the same story is told in both sonnets, its purpose presumably to provoke us to more serious contemplation. Leonardo da Vinci said “The joy of understanding – that is the most noble of pleasures.” Therefore to find the bath sonnets pleasurable it is no good approaching them with a sense of traditional dogma because you will be puzzled by them and find them disappointing in comparison to what has preceded. The template for these epigrams by Marianus Scholasticus is an ancient Greek verse, its subject matter a perfect foil for the story Oxford wanted to tell of events that took place in the spar city of Bath, verse he considered an appropriate vehicle for transporting the emotional maelstrom that infected his head in the summer of 1574. (S147) My love is as a fever, longing still For that which longer nurseth the disease, Feeding on that which doth preserve the ill ………. Past cure I am, now reason is past care My thoughts and my discourse as madmen’s are ………. Quite understandably (as he had suffered so) Oxford didn’t want those events relating to the summer of 1574 to pass by as if nothing of any consequence had happened, therefore he considered The Bath Sonnets a fitting finale, a sting in the tale perhaps, composed of words ultimately to be published beyond the grave, words the Elizabethan state would have condemned as heresy, words cleverly wrought within the framework of myth – thereby offering himself some indemnity from prosecution. Firstly I shall take an overall look at this mythological allegory. Cupid a little Love-God born of desire is a love-child but also a deity, so his brand burns with a holy fire of love. While he sleeps, the fairest votary with her maiden hand takes advantage and plunges his love-kindling brand into the cold valley-fountain, creating an eternally heated spring. While our love-stricken poet seeking salvation muses upon the effects of these seething waters, though finds no cure, until he glances at his mistress, when loves brand is re-ignited as he finds himself immersed in her eyes – bathing in the very place Cupid first found desire. Now I shall look at these sonnets through the eyes of our Tudor-trinity. Cupid/desire – represents the Love-God Wriothesley. Elizabeth is portrayed as a maid of Dyans (the goddess of chastity) while the malcontented lover is a characterization of Oxford. The Nymphs represent Elizabeth’s ladies-in-waiting. As the city of Bath is mentioned four times we know that’s where these events take place. Oxford-speak: He defines this in (S76 & S105) as ‘his invention’ prevalent in the Bath sonnets and what determines that they relate to real people and are not pure fiction. It is not too large a leap of the imagination to realize that in (line 8) the words ‘sovereign cure’ must surely relate to a monarch, especially as two further references to the queen follow in (lines 19 & 22) of course it is ambivalent language (as all the sonnet’s are.) As we have seen in (S147) once again our poet casts himself as a victim of love, for although it appears a known practice men will experience seething waters as a hopeful cure for ‘strange maladies,’ he finds himself a pawn in the process of love, because the moment he catches his mistress’ eye, new-fired desire triumphantly points him towards his prize, so to his torment he endures love as an inescapable disease, at the mercy of a voracious she-wolf. (Line 10) begins with the words ‘The boy for trial’ which of course is exactly how Oxford perceived the situation of his infant son, although he may wishfully have thought of him as a prince in waiting, his future was in fact completely uncertain with Oxford having no say whatsoever about his upbringing, his guardianship, or his education. The little Love-God was therefore in reality a bastard infant prisoner, a boy for trial, who lamentably would find his future decided behind closed doors. Oxford whose input into the English language was extraordinary, was well ahead of his time using the term Love-God in (line 15) it being so similar to the term love-child, while simultaneously referring to his son who in ‘his invention’ he frequently describes as either prince, monarch, king or alternatively as divine, deity or God. While in (line 19) we find the idiom ‘The fairest votary’ tantalisingly close to the ‘The imperial votaress’ of ‘A Mid-Summer Night’s Dream,’ which was known as far-back as Jacobean times to be an allusion to Elizabeth I. Three lines later in (line 22) there miraculously appears a virgin hand, of course another reference to Elizabeth. While a heavy-hearted Oxford describes himself in (line 26) as ‘my Mistresses thrall’ words which harshly translate ‘to my mistresses’ slave,’ someone to whom he infers elsewhere in the sonnets that he has to provide sexual services for. Dutiful deeds described in (S151) as ‘my gross body’s treason.’ (S149) Canst thou, O cruel, say I love thee not, When I against myself with thee partake? (S151) But rising at thy name ………… …….. contented thy poor drudge to be To stand in thy affairs, fall by thy side ………. Her ‘love’ for whose dear love I rise and fall. Trying therefore to seek the overall meaning of The Bath Sonnets I would say this; Oxford while fleeing for his life had travelled to the continent in an illegal act (because somebody of his position needed a license to do so.) His return from Brussels to Bath was therefore effectively by royal command, a journey during which he prayed Elizabeth would have a change of heart about their future, because his words record that he considered her as “vowing new hate after new love bearing” while in the process breaking two oaths she had made him, and in response to these ‘perjuries’ he cried out “all my honest faith in thee is lost!”(S152) Therefore he hoped for redemption while anticipating ‘a sovereign cure’ though ultimately no lasting cure was found, although he did witness a great love towards his son (by many legions of true hearts) though his dreams and his son’s destiny were literally quenched by Elizabeth, when as ‘the general of hot desire’ he was ‘by a virgin hand disarmed.’

– A Metaphysical Poem –

Existentialism rocked-up along time after the Earl of Oxford but what he thought was – there is no time like the present, before writing these lines.

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow, creeps in this petty pace from day to day, To the last syllable of recorded time; when all our yesterdays have lighted fools their Way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle! life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player That struts and frets his hour upon the stage, and then is heard no more; it is a tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury – signifying nothing.

It was also a long time after Oxford graced the world before Samuel Johnson coined the phrase ‘metaphysical poets’ nevertheless our author uninhibitedly wrote.

Let the bird of loudest lay On the sole Arabian tree Herald sad and trumpet be, To whose sound chaste wings obey.

The major drawback with these words was of course that nobody understood what the fuck they meant! While this misery was compounded because once having read them, one couldn’t then unread them, they then became an earwig in our heads. Even before the number became unlucky, Oxford posted humanity thirteen obscure and possibly indecipherable envelope verses, but naturally there was method in his hubble-bubble madness. He wanted us scratching our heads, analyzing, struggling and pontificating over these conceit’s – his purpose, to focus our minds so we would more readily absorb the information contained within the more important second section – known as the Threnos, words which reveal the conundrum at the center of his life, but mercifully in the final verse of the first section known affectionately as the ‘session’ we find ourselves reunited with our sentimental, romantic poet.

To the Phoenix and the dove Co-Supremes and stars of love.

Leonardo wrote ‘What is fair in men doesn’t last, old age creeps up on you, nothing’s more fleeting than the years of a man’s life.’ But in respect of the fair-youth, Oxford has proved the first part of this statement to be untrue, because the sonnets as a monument are the living record of Wriothesley’s memory, posterity therefore conceives the fair-youth as immortal – precisely as Oxford intended. I am not necessarily suggesting that Oxford read Leonardo’s words though at the age of fifty and being infirm he was certainly aware that anything that needed to be said – needed to be said soon. He was also following the Essex Rebellion mindful of the Queen’s low self-esteem, having been in her company when Robert Devereux (the Earl of Essex) was executed. As the story goes the Queen (trying desperately hard to occupy herself) took to the virginals beginning to play, an action provoking Oxford’s wit, for he turned to Sir Walter Raleigh and whispered “When jacks start up heads go down.” In more youthful days, days of heady romance Elizabeth had played music Oxford had composed, a fact confirmed in (sonnet 128) where he even mentions the word ‘jacks.’ Do I envy those jacks that nimble leap To kiss the tender inward of thy hand, Whilst my poor lips, which should that harvest reap, At the wood’s boldness by thee blushing stand. These then were the circumstances that led Oxford to this esoteric prophesy – first published in Robert Chester’s Loves Martyr in 1601. They are words that speak of familiar protagonists, our Tudor-Trinity.

– The Phoenix and the Turtle –